James Ellis Ford first found fame, alongside close friend Jas Shaw, as part of Simian Mobile Disco. In the 2 decades since then, James has gone on to establish himself a as super producer, working with an incredible, long, long, list of critically acclaimed, and commercially successful, outfits. From Arctic Monkeys and Gorillaz to Soulwax and Jesse Ware. I think, most recently ably assisting hotly tipped South London rave `n` rollers, Fat Dog. In May of this year James issued his own solo debut, The Hum, and as a consequence I got the chance to interview him for Electronic Sound Magazine. The published piece, which you can find in the marvellous Modular Synthesis-fixated Issue 104, was a fairly short “Under The Influence” feature. James, however, like so many of the artists that I’ve been lucky enough to talk to, was super generous with his time, and via Zoom he gave me a guided tour of his utterly enviable attic studio. By the end he’d convinced me to invest in a couple of reel-to-reels, and the conversation had run to just under 2 hours…

I have to say that the album is an incredible achievement. For you to have done that all on your own is really impressive.

Thank you. I appreciate it. It’s something that I wanted to do, to challenge myself. Push myself out of my comfort zone.

I listened to the album and made some review notes – I always read press releases after I’ve made my own notes – and one of the questions I had was about the tape loops, since they sound so much like Eno & Fripp. So when I read that they were created in exactly the same way as on No Pussyfooting I was super impressed. It must have been great fun.

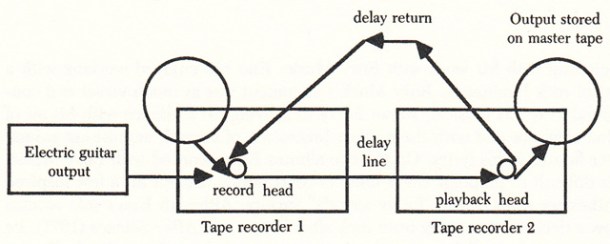

So, I’ve got these Revox reel-to-reel machines over on this side of the studio, and basically you record into this one, and then playback on that one, and put the output back into the first.

To be honest, I’ve got mountains of this stuff. I’ll often come up here, to my studio, of an evening and play around, to just entertain myself. It’s really relaxing and enjoyable to create these evolving soundscapes. So sometimes if my wife is watching TV I’ll sneak upstairs. When I’m messing around, I’m always recording, just out of habit really.

How did the album come about?

I found myself with more free time, longer than normal between my fairly crazy schedule, so I had the chance to knock around up here for the first time properly in ages. Jas Shaw, my partner in Simian Mobile Disco, got sick, and I couldn’t be in the same room as him. Then we had the pandemic on top of that. This gave me breathing space that I hadn’t had in years, and so I started to take some of the tape loop sketches and make them more than that. That was the start of the album.

The first influence I’ve chosen is a place. This place. My home studio. I’ve only had it for about 5 years. It’s in my attic, and contains all of the equipment that I’ve collected over the years. Everything from modular synths, to a lot of the stuff we used in SMD, like the Arp 2600, a drum kit, a vibraphone, a bunch of guitars, the tape loop station. I built it myself and I’ve got everything wired up. For example, the drums go though these pre-amps, so to record the drums I just have to turn the tape machine on and start playing. It takes out all of the faffing around, that you get in a lot of studios.

So if you get an idea you can just switch on and go for it?

Exactly. I’ve never really had the space to make my own music before. I’ve always been in studios on other people’s dimes, and I’ve always been busy, so I’ve never had much space time-wise either. Now that I’ve got this studio I’ve got a space where if I’ve got any downtime what so ever I can come up and very quickly I can have a mess around and get some stuff going.

How difficult was it to get all the equipment speaking to each other?

It was difficult, and it took me quite a long time, but I do love the technical aspect of it. There`s a slightly sick pleasure that you get from setting up a patch bay. It’s akin to my grandad taking old clocks apart and putting them back together again. My dad’s also the same. I think there`s a tinkering gene.

But if you get to the root of it that means that you really understand how the equipment works, and that surely makes a huge difference to the music that you make.

Exactly. Also to a large extent a lot of ideas begin with me trying to figure out if a piece of gear is working. I’ve plugged it in, and I’m trying to get it going, trying to get a sound out of it, and something strange will pop out, and I’ll be like “Oh, I like that” and be able to record it. Me kind of feeling my way through, getting a process or a chain of equipment working. That’s often the spark.

Also I’m essentially quite a shy guy, so to be able to do this in my own little bubble, my own cocoon, in my own house, without anybody else being able to hear me. For example, to sing for the first time, I probably wouldn’t have done that in another studio, in front of an engineer or anybody else. This studio allowed me to do this. It`s the first time in my life that I’ve had a place like this, and that’s probably why it’s taken me so long to make my own record.

It must have taken some bottle to sing, even on your own, if you’ve never done it before?

The hardest part of the whole process was to just get over myself a bit. I think everyone does this, but I put myself in this little box – I’m a producer, that’s what I do, I help other people make music. The melodies come fairly easily, but combining that with a lyric and using my voice, it was a challenge, and a mental challenge as much as anything. To pull myself out of that box, and ask why am I not the person who would sing on a record? To challenge myself in that way seemed like one of the boldest things I could do.

Your lyrics are obviously very personal, so I’m sure sharing them was another big step.

I’m still finding it tough knowing that other people are going to hear it, but I got really into the process and I really enjoyed doing it. I started to really enjoy writing the lyrics. I’d play stuff to my dad, and to my manager, and it was very nerve-wracking in the beginning. It’s not going to be a huge record, but that was never the point.

One look at your production credits – the people that you’ve worked with – and anyone will see that you’ve got nothing to prove.

That’s given me a bit of freedom in my head, to do something like this. You know when your eggs are in one basket, that kind of tension and restriction hold you back. Now that I’ve had a bit of success in some areas, I can try to view this as “just another record.”

Try not to over think it I guess. Not to put too much weight on it. Do it just do it because you enjoy doing it.

Trying not over cook it too. A lot of it was first takes, you know, first thought, best thought, even with the lyrics. Most of the records that I love have a kind of loose feeling about them. I know that I can make something sound really big and really polished, but this was about doing something different.

It’s obviously a very personal record, a little bit eccentric, a little bit psychedelic in places. It’s definitely heading for at least cult status (laughs). It’s very much like a long, lost Brian Eno LP.

I can’t lie. Those early Eno records have always been a huge influence, as well as that whole Robert Wyatt, Canterbury scene. That takes me nicely on to my second influence, which is my dad.

Me and my dad have a very good musical relationship. We still send each other music. He used to play in a band, just a local band, but because of that I had this space in my teenage years, of like a basement with a drum kit in it and a synthesizer and the chance to think about music, in the “making it” sense. So I’ve been playing in bands since I was 11. Also, my dad’s music taste is what I’ve found myself reverting to. I didn’t really like it at the time, but my dad is a big Canterbury, progg-y fan. I grew up with bands like Caravan and Gentle Giant, and Kevin Ayers, Robert Wyatt, Eno. That’s all in my musical DNA, from just being in the background when I was growing up. I also remember things like Ivor Cutler, things with a sense of humour. That’s the stuff I’ve gravitated back to now. The first person I sent my solo music to was my dad.

It’s really nice that you have that kind of relationship wth your dad. Just out of interest, if you’re bouncing music back and forth, what sort of stuff have you been sending to him?

Actually at this point it’s more him sending me stuff. My dad will send me new bands that I’ve never heard of. We go to the Green Man festival together and he’ll know every act on the bill, and be recommending those that we should see. He’s also very into Hi-Fi. The music lover part of me was just part of my upbringing. My mum too, to be fair, but more my dad.

Is your dad a multi-instrumentalist?

He plays guitar and bass, but he’s not a trained musician. He’s more of a dabbler. There have been a few people in my life who have introduced me to different areas of music, but my dad was the first, and a very important one.

My next influence is a life event. One of the biggest things has been my best friend and musical collaborator, Jas Shaw, getting sick. I’ve always been looking to be pretty busy, producing for other people, but any extra time I had I would be making music with Jas. Jas is a brilliant, incredibly intelligent, funny person, who always comes from an oblique angle, in music, in everything. Then suddenly we were faced with the situation where I couldn’t be in the same room as him anymore. He’s immunocompromised, and been through a lot. His illness and absence created this big hole. We used to spend a huge amount of time together, not just making music, but gigging, touring and hanging out.

I’ve always felt that it was important to do something outside of production, for myself, and in the past that was always Simian Mobile Disco. Jas` health issues are up and down, but hopefully we’re going to get together and make another album again soon.

The pandemic must have been terrible for him.

Jas is incredible. He’s been through the absolute worst and he’s still going through it to a large extent. He’s still making music. He lives, funnily enough, out toward Canterbury. He’s with his family and he has a studio in a barn out there. He’s constantly inspiring to be around. He’ll always come up with weird and wonderful ideas for records. He has a weird way of approaching things. He’s like a Brian Eno to me. He has these sort of strange thought patterns. He’s a brilliantly creative chap, and a lovely man to boot. At some stages in our lives we’ve spent more time with each other than with our respective partners. We know each other really well. It’s very odd to go from spending that much time with someone to not seeing them. We’ve been through a lot together.

My 5 year-old son has been an influence in a number of ways: The urge for me to be present in his early years, so working more from home, being around. This brought a domesticity, which I think is evident in the new record. A lot of it was made in little, snatched moments, in between being the dad of a young kid. The sleeplessness. All of those things that go with having a young child. There’s suddenly a time-crunch that comes with that, which whenever I had any free-time, this burst of creative energy.

I know that feeling. I’ve got 3 sons – they’re older now, 2 are at uni – but when they were small, I tried to do something creative with every spare minute I got. To be honest, now that only the youngest is with me, and I’ve potentially got bigger windows of time, I`m actually at a bit of a loss as to what to to. Without those time constraints I feel a bit lost.

It’s a common thing in production. I always think that it’s the thing that makes you finish is time. Time is the commodity that runs out. You do the best things that you can within the allotted time… and that’s why you get the Fleetwood Macs, where you’ve got unlimited time, nothing gets finished, and you just go bonkers. I’ve been involved with a few projects, some of which are still unreleased, and the person whose project it is doesn’t have that time restriction, so these projects go on for years and years. I think you summed it up perfectly. Having a small child, you’ve got to make the most of these little windows. That means that you’re efficient and productive. You can’t procrastinate. You just get on with it. That’s one way that my son has influenced how I work, but also my wife is half Palestinian, so I’ve been interested in understanding their background. Pre-pandemic I got the chance to go to Palestine, and I fell in love with the local music. All the microtonal stuff, and the strange scales they have, which are different but have similarities with Indian classical music, where things are done in these kind of modes. I also discovered Habibi funk, which is people from that part of the world trying to sound like James Brown and instead coming up with something unique. On the new album, the track, The Yips, is heavily influenced by the music that I heard on that trip.

Frank also made the artwork for the album. It’s an inverted photo of a little art experiment that we did, blowing down felt-tip pens.

Do you think that being a dad has made you braver? I’m also quite a shy guy, and I found that becoming a dad, where before I might have hesitated about doing things, as a dad, I was forced to step up and face challenges and difficult situations. I had to try to lead by example. You know, you’ve been talking about being hesitant about singing for example and I was just wondering if being a dad sort of forced your hand.

Yeah that definitely plays into it. It maybe makes you care a little bit less about what other people think.

I can’t tell my kids not to not be scared, if I’m dodging challenges and responsibilities.

It definitely makes you think about the person that you are in relation to them. In my lyrics as well there’s quite a lot of me being in my family bubble, and then all that crazy existential shit that’s happening in the world. Obviously when you’ve got a kid, you’re thinking about what the future’s going to be like for them.

There was one lyric that really intrigued me – “Stepping outside the stories that we tell ourselves” – where does that come from?

It’s partly about me stepping out of the comfortable “producer” box, but deeper than that it’s about the stories we put in place to make sense of reality. I’ve been reading a lot about the nature of consciousness, and how to get beyond the narrator in your head, and greater understand the real nature of what is around us. Within the psychedelic experience a lot of that stuff gets broken down. There’s still such a lot of that part of the mind to be explored.

The key thing about doing psychedelics is that they make you realise that there’s more than one way to see anything, that the way you see things isn’t necessarily the way that things are.

Exactly. That’s the root of it. They are stories that you tell yourself. Your mind is trying to rationalize all the data and information it’s receiving.

My next influence is a piece of equipment. This, a bass clarinet.

That’s pretty big. Are all bass clarinets that big, or is that an exception?

No. This is pretty standard. It looks and sort of sounds like a goose. It was quite a big part of the new record. All of the melodies were written and played on this. I’m not by any means a bass clarinet player. I learnt the flute when I was a kid. I kind of hated it, but dutifully learnt the fingering and blowing technique. I’ve always loved the sound of a bass clarinet – partly from my Manchester days. When I was in my first band I was also playing with Graham Massey – from 808 State – in collectives called Toolshed and Home Life. Graham introduced me to a whole load of creative people, like Paddy Steer, who is an incredible, bonkers musician, and music like Moondog, which was a revelation for me. A lot of that is bass clarinet stuff. Graham would also sometimes play bass clarinet. So, one day I saw one on eBay, took a punt on it, and taught myself to play it by watching Youtube videos. This was around the time that I was starting to make the new record. I was just really getting into learning how to play it, and that’s a regular pattern for me – trying to get to grips with something and within that process some music is generated.

Learning something new must be inspiring in itself. Making new noises.

Yeah. Challenges, frustrations, and then little successes.

You can hear the reed in places on the album. There are odd bits of free-jazz skronk – as Lester Bangs would have called it – snippets, snatches of early Roxy, Andy Mackay. There are a lot of treated drones. Are they all coming from the clarinet?

Yes.

The record sounds so much like Eno and Fripp that I assumed that everything was being generated from a guitar.

Its bass clarinet put through a Mutron Phaser. I love Roxy, and Lol Coxhill, and I’m also a big fan of Jon Hassell. The Fourth World stuff that he did ticks a lot of my sonic boxes.

For most of the record it’s not recognisable. You only hear a saxophone-like noise breaking through occasionally.

That was intentional. I like it when you can’t quite pinpoint what’s making the sound. On a lot of records that I like you’re asking, “Is that a voice, or a sax?” I love that thing where it’s quite treated.

It makes the music hard to review though. I can amend my notes now (laughs).

There is a guitar in there. It’s a semi-acoustic, a Gibson 125, that I play, with an ebow. That fed through the phasers sounds quite similar to the bass clarinet. It’s also in a similar register to my voice. The drones are a melding of these different timbres.

My next influence is Frippertronics. The tape machine set up. I always loved Evening Star, and those early Eno records. When I’ve been working all day, listening to music, producing. It’s stuff like that, and Jon Hassell and Harold Budd that I turn to, to unwind. You can do tape loop stuff with delay pedals. I’ve done that in the past – but when you read about Eno and Fripp’s experiments you can find a diagram of their set up.

I`m sure I’ve seen a photograph with tape running around the studio furniture, chairs and stuff.

Exactly. So basically the distance between the two machines is the length of the loop, but it’s hard to keep the tape in tension so you have to run it around mike stands and chairs to get different lengths. Once you actually try it with the machines it’s much more unstable. There’s a real physical element to it. The tape is wobbling and you get this sort of motion. When you do it with a digital delay, or on a computer, it doesn’t evolve in the same way. As the tape’s playing you’re adjusting it. It’s very warm. I have a lot of this stuff and I think that I’ll make more of them available once the album is out.

What I tend to do is get the thing going, and then you’re sort of riding this wave. You don’t want it to feedback on itself too much, because then it gets out of control, and gets all distorted. At the same time I’ll be playing into it with keyboards, or vibraphone, and then play over that with a guitar, this all then feeding back on itself. It’s hard to change key. You’re kind of restricted in the tonality, but there are a couple of other effects in the chain, to add different flavours. It sort of disintegrates. Certain frequencies get heightened, and you can get some really interesting soundscape stuff. It’s just endless fun. It’s definitely a long game. The pieces on the new album are edited down versions. The originals are more like 20, 30 minutes long.

Why The Hum? Is that the drones?

It actually comes from an article that I was reading about this phenomenon of unexplained noises. The piece contained a little map of where these things have been heard, all over the world. People don’t really know where the sounds are coming from, but it can be like a geological thing, or the wind in a big industrial chimney, or a steel works miles and miles away. There was one story about a woman in Yorkshire who hears a noise in her house, only she can hear it and she only hears it in the house. There are instances of this all over the world. People are trying to explain where the low frequency vibrations are coming from, and the collective word for them is “The Hum”. This slightly sinister unexplained noise. People having kind of religious experiences in the context of these super sub-harmonic vibrations.

These frequencies will obviously activate certain centres in your brain. They give you goosebumps and stuff. A lot of those big old pipe organs, used in churches, have sub-harmonic keys. Keys you can’t hear, but instead they give you an eerie feeling. When people couldn’t explain it, they thought maybe it’s God.

Have you read Harry Sword’s book, Monolithic Undertow? In the opening chapters he visits various holy, sacred sites around the world and investigates their acoustics and natural harmonics, talking about how ancient ceremonies incorporated similar effects / phenomena to those that you’ve described. Resonance chambers, both natural and man-made that create frequencies that make people feel weird, like they experienced something otherworldly.

I haven’t, but I will now. I went to this experiment at The Barbican, about 15 years ago. They had a huge pipe set up across the back of the room – like a sub-harmonic generator – and you had to fill in a questionnaire. For some questions the pipe would be on, for others it would be off. They were trying to see if the sub-harmonics influenced how you felt and how you answered the questions.

Well, that’s got to be a given. Music totally influences your moods.

Yeah, but music you can’t hear?

Fascinating stuff. Well, your album’s not eerie at all. There are no creepy bits on it. It’s all love songs.

Pretty much. I’m a soppy git at heart.

James Ellis Ford’s The Hum, and his tape improvisations, can be purchased from Warp.

You can pick up the latest issue of Electronic Sound here.

Discover more from Ban Ban Ton Ton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.