I was always jealous of the Reid Brothers, William and Jim, The Jesus & Mary Chain. Together with Primal Scream they seemed part of a big group of friends who were always sharing, showing off cool music. Digging up cult LPs from the `60s and `70s. Dropping artist names and album titles in interviews. Brandishing, clutching rare sleeves. They covered Syd Barrett, Can, and Bo Diddley. Giving a few of their influences away (1). All I had was my mate Dave. All Dave had was me. No one was sharing this treasure with us. We were having to make do with buying blind, taking chances on what we could find in Croydon’s cut-out and bargain bins.

I picked up a copy of JMC’s debut 45, Upside Down, because I’d read about the riots at their gigs in the NME. The inky compared them to the Sex Pistols, a new angry energy, a new revolution – dark, malevolent and violent. To be honest, I didn’t know much about even The Pistols back then (2). Together with the band’s follow up 45, Never Understand, it became a call-to-arms when we drank and danced at an indie club called The Underground. An excuse / chance to charge about like headless chickens, lashing out with arms and elbows in a crowd of similarly smashed young men.

Dave bought the debut LP, Psychocandy. We were still in 6th form, studying for A Levels, with only Saturday jobs. Both of us had limited dough, so we didn’t duplicate much (3). Tracks like The Living End were a furious filthy amphetamine rush of angst and fury, that drew on The Ramones, The Stooges’ Raw Power and Metallic K.O. and threw in the odd Einstürzende Neubauten industrial clank (4). The lyrics spewed nihilism, narcissism and self-loathing in equal measure, while shouting about motorbikes and leather boots (5). It was easy to see how stuff like this might set off a suitably cranked up crowd. The feedback was mind-bending, but not everything was screech-soaked (6). To be honest, I was just as keen on the softly strummed numbers. Songs like Cut Dead. Strung out surf. Part Beach Boys. Part Velvet Underground (7). But even they mixed, equated, love and violence. Where the objects of desire were crazy kittens from exploitation movies and video nasties. The sort of films screened at Scala all-nighters (8). Twisted S&M nursery rhymes. Where wired femme fatales ran around with sharpened pointed blades, pissing everybody off. Me and Dave pictured people dressed in retro / second-hand `60s chic. Speeding behind sunglasses. Imagined the sort of party we were never invited to (9).

Drums hammered out a primitive Mo Tucker beat. Reverb rivalled Sun Studios’ rock ’n’ roll echo. The basic bar-chord riffing was rudimentary, the couplets sometimes clunky and the solos, occasionally fluffed, fumbled. Really, it was the brothers’ sheer conviction and incredible self-belief that carried them to success.

By Darklands’ release, in `87, we were both big fans (10). The lyrics were gloomy, but the production too bright, too clean, too pop to be goth. The rock more straight forward than before. Shedding the shredding and instead touting strutting tremolo twanging and 6-string nods to Echo & The Bunnymen’s Will Sargent. The Velvet Underground were still in there, but so was Lee Hazlewood. 9 Million Rainy Days featured stoned Stones’ Sympathy For The Devil “Ooh oohs.” There’s a version of On The Wall that sounds like Joy Division, or New Order. About You was a beautiful ballad. Only Everything Is Alright When You’re Down screamed and shrieked. Songs such as April Skies were loud, upbeat, over-amped Americana anthems. Happy When It Rains was huge. JMC at their most joyful. By 1988, and the single Sidewalking, however, we’d hightailed it out of there, dropped an E and jumped on another bandwagon.

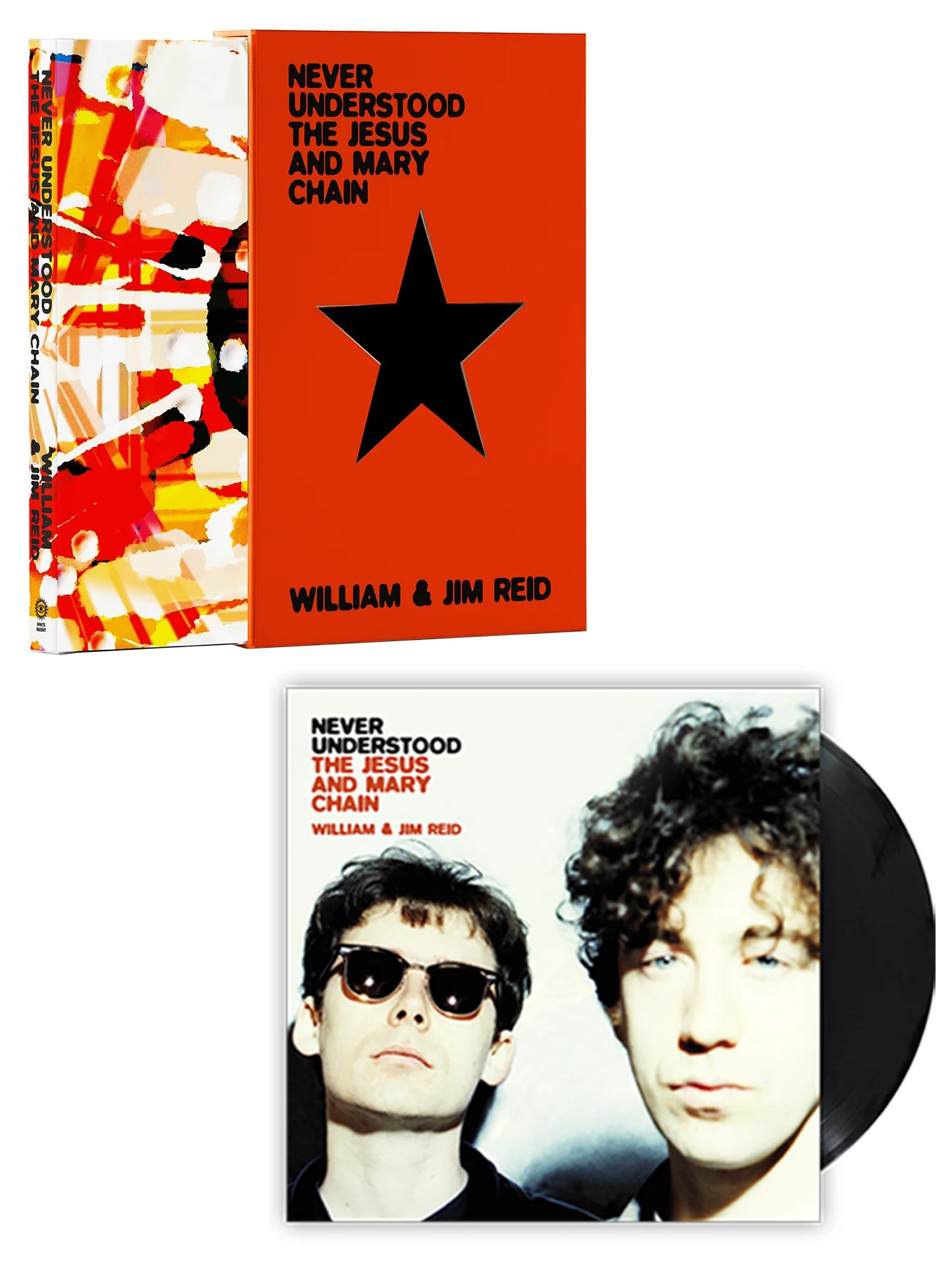

I’m writing this now, in part, because I’ve just read, Never Understood, William and Jim’s book. The brothers’ biography, dictated to writer Ben Thompson, details their working class childhoods, acid-eating adolescence and how the siblings used music as a means of escape. Initially mentality, and through dogged determination, eventually, physically. Leaving East Kilbride far behind. It describes Indie imprint fallouts and major label frustrations. Substance and mental health issues. The pair seem a bit pissed off in places for not being cited as sources of inspiration / godfathers during shoegaze’s boom. The sublime, fragile Just Like Honey surely deserves some such accolade. The Reids getting ridiculously romantic, while their raw wall of sound gives way to a sweet soft focus sheen. Borrowing from The Shangri-Las and countered by ethereal female harmonies (11). However, from the outset, perhaps fuelled by alcoholic arrogance, they baited both audiences and the music press, so the idea that they’d be championed – after calling everyone cunts – might be expecting a little too much.

The Reids were always feuding. Famously fighting on stage. It’s kind of telling that the book, presented as a kind of oral history, with the each brother recounting their side of events, has been put together from individual not joint interviews. In the past, William came across as the more unpredictable, the more dangerous of the two, but now appears the most balanced. Willing to admit at times he was wrong. Both are candid and brutally honest. Neither is illuminated in an especially good light. But then if I sat down and wrote my life story, I, as sure as shit, wouldn’t be either. Jim seems unapologetic and unrepentant. Still full of a frontman’s “fuck you.”

Listening to the acoustic versions of William and Jim’s songs, the demos that came as b-sides on 7” double-packs, I’m forever 17. Driving late at night, through Croydon’s deserted, silent streets, riding shotgun in Dave’s battered Ford Escort. Looking, searching for our own way out. Something about those early songs smacks of innocence being lost. Mirroring our own teaming teenage experiences / adventures. I was done up like Morrissey at Top Shop. Dave was a ringer for James Dean.

For Dave & Michelle…

NOTES

1. John Lee Hooker was likely another. Shake starts off as a blues, before it becomes a guttural howl. The super radio-unfriendly robotic rockabilly of Kill Surf City clearly loves The Cramps.

2. The Malcolm McLaren-like stoking of the concert violence, by Creation Records’ Alan McGee, is one of the most interesting parts of the biography. Just like The Pistols it proved ultimately counterproductive as they couldn’t get booked.

3. As an adult / a working stiff I’ve gone back and bought copies everything I can remember that we played together.

4. I, of course, didn’t know about any of these references, or others mentioned, until much later.

5. This song inspired the Gregg Araki film of the same name.

6. Listening to JMC in retrospect, and having recently interviewed The Cocteau Twins’ Robin Guthrie, it’s been really interesting to note similarities in the two bands music. Both William Reid and Guthrie came from a place where they couldn’t “play” anything like proficiently in the conventional sense and both instead used their guitars to generate “noise”. Reid turned the amps up to 11, creating with distortion and feedback. Guthrie’s trick was to play really loud, but record quietly, and contrast that with playing softly and recording really loud. Guthrie coincidently worked on several Gregg Araki soundtracks.

7. Some Candy Talking was, of course, JMC’s homage to The Velvet Underground’s Heroin.

8. The Scala was a cinema in London’s Kings Cross, home to a film club, host to all-night screenings of modern arthouse movies and cult classics. Back in the days before E, for us it provided an alternative Saturday night out. Janes Giles wrote a brilliant book about The Scala, which was later expanded into an equally brilliant documentary.

9. Dave and I did start to go a ton of Creation Records and “shambling bands” gigs.

10. We saw the band live a few times, the last being the Rollercoaster tour, at the Brixton Academy in `92. By then, to be honest, I was more interested in Dinosaur Jr – whose Freak Scene and cover of The Cure I heard on John Peel and span over and over – and My Bloody Valentine, who had finally released Loveless, and promised / threatened to play at a mind-altering volume.

11. The song now synonymous with Sofia Coppola’s Lost In Translation.

William & Jim Reid’s Never Understood is available directly from White Rabbit Books.

Discover more from Ban Ban Ton Ton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.