Dub Syndicate’s recording career can be divided into three distinct phases. The first, from 1982 to 1985, was an experimental, studio-based project, driven almost exclusively by the imagination of Adrian Sherwood. These captured the On-U Sound co-founder, and now legendary producer cutting his teeth, creating rhythms with a rotating assembly of talented friends and visiting guests, in various studios in and around London. The sessions resulted in the long-players, The Pounding System, One Way System, North Of The River Thames, and Tunes From The Missing Channel. In 2017, these were the focus of a reissue program, titled Ambience In Dub. Next came a period of collaboration between the UK and Jamaica, where drummer Style Scott built the rhythms in Kingston, while Sherwood took charge of overdubs and the final mix, largely at his own studio based in Walthamstow. These albums were all strictly dub, and released via On-U Sound. The final chapter then found Scott leading a powerful live band, and moving the group’s output more toward songs. More reflecting their on stage performance. Scott issued these recordings on his own label, Lion & Roots, until his murder in 2014.

On February 28th, On-U will release a new reissue package focused on the band’s second phase, under the moniker Out Here On The Perimeter 1989-1996. I had the pleasure / honour of being asked to pen the sleeve notes. We structured that text to tell the story of Scott, who alongside Sherwood was not only the driving force behind Dub Syndicate, but also a musician who without a doubt played a major role in the evolution of modern reggae, and whose contribution remains criminally, largely unsung. To read that story you’ll have to order the reissues, however, below is something from Sherwood, put together from Zoom outtakes, where he provides a candid, potted history of both On-U Sound and Dub Syndicate.

Text taken from Adrian Sherwood in conversation.

I was only 19 or something, but I’d met a lot of musicians while working with Chips Richards at the label Carib Gems. People coming in and out the door, people who knew Chips. I was just starting out. I didn’t know anybody, so I met the musicians, and I also met gunmen, you know. Seriously, they all came to say hello to Chips when they were in London. Along with the musicians, people who were like real bad boys from Kingston. I didn’t know who was a musician or not to start with. Then I met Prince Far I in Birmingham. He was on a tour promoted by the soundsystem Quaker City. He was with Fish Clarke and Errol “Flabba” Holt. Fish came with us to London, and around this time I decided to run my first ever session.

I met Clifton Morrison, Bigga, the keyboard player, through my friend Glenmore Williams Jr. – who was the father of Ari Up‘s twins – when we all squatted together. Clifton’s cousin was Crucial Tony. They’d never been in the studio before. Then, near where I lived, there was a bass player called Clinton Jack, a Calypso bass player. Plus my friend, Dr. Pablo, Peter Stroud. I hired the studio, and I paid everybody. I gave them all 20 quid, in Fish’s case 50, to play – which doesn’t seem like a lot of money, but the average wage in those days was about 30 pound a week. I spent 200 pounds making the record, and then things collapsed at JA Distribution, the company I ran with Joe Farquharson. We worked on such small margins. We were in a lot of trouble. So then Dr. Pablo and I started Hitrun Records, and we put together the album Cry Tuff Dub Chapter 1, by overdubbing sound effects and stuff on a set of Prince Far I rhythms. This was in March, 1978.

Far I wanted to do another tour, so we cobbled together a band London. We did a couple of gigs, the band didn’t have a name. It was just Prince Far I. The first one was at The 100 Club on Oxford Street. We did that with virtually no rehearsal, just jamming, but it was an amazing show. Far I was just running the mic over everything. People still remember, talk about that gig. It was the first one I ever mixed. From there, `79, we planned to do a tour. The budget to bring over a whole band from Jamaica just wasn’t possible, instead we brought over just a drummer. We were initially gonna bring over Santa, Big Youth`s drummer, but at the last minute he couldn’t come. Far I said “I’ve got this new drummer who I’ve just recorded. He’s just fresh out of the army from in Jamaica. He’s been working on the north coast as a waiter in Montego Bay.” I was thinking, “Yeah, right. This guy’s probably some kind of tourist”, but when I heard him he was incredible. That was Style Scott.

We started rehearsing at Gangsterville on The Harrow Road – the same place where Tradition were based, and where Aswad rehearsed – and we were now touring as Prince Far I and Creation Rebel. We recorded Dub From Creation, Rebel Vibrations, and Starship Africa all around the same. I was really focused on dub, but Tony wanted to sing, and that resulted in the album Close Encounters Of The Third World. Tony wanted Creation Rebel to be more like say Aswad. I’d befriended Alvin Tropical – lovely guy – who was friends with King Tubby, and through him, when Prince, now King, Jammy came over to London we paid him 500 pound to mix that album.

Hitrun was in a lot of financial trouble, so the next year I started 4D Rhythms with Chris Garland, who was managing the Nottingham band Medium Medium. We did another tour later that year called the Roots Encounter Tour, and Far I brought Bim Sherman over for the first time. Far I, Bim, Prince Hammer, that was the tour. On that tour, we had members of The Clash, Public Image, and most notably Ari Up in the audience. Ari and me became very close friends. I really loved Ari so much, and we got invited to support The Slits, who were touring with Don Cherry at the end of 79. It was the tour to promote The Slits album, Cut. At the beginning of 1980, we also supported The Clash on a load of dates, but then Style had an acute appendicitis in Glasgow the night before our main show at The Rainbow, and that basically was the end of Style’s involvement with Creation Rebel.

We carried on for a couple of LPs, but it was a disaster financially for me, and then then in the space of no time at all Prince Fari was murdered, and our bass player, Lizard Logan, thrown in prison. That was the end of the band. I was just so fucking pissed off with everything, there was nowhere really to go. I vowed that I wouldn’t do any more Reggae. To be honest, I was so upset by Far I`s murder. I was so disillusioned. I was in debt up to my eyeballs. I’d secured a loan against my mum and stepfather’s house.

I was still trying to pay those debts off, but by now we’d started On-U Sound. On-U was like 3 years old. We’d done, the Maffia LP, the wonderful album Learning To Cope With Cowardice, New Age Steppers… cobbling all these records together. We were starting to get noticed, and Daniel Miller at Mute asked me if I could remix Depeche Mode for him. Dan had been my friend for years, ever since we were both teenagers selling records out of the back of our cars. The whole idea of On-U, initially, was that it was going to be a like a production house. We were going to work on projects and license them to other labels. We didn’t plan to put any records out. When it started it wasn’t just me. There was Martin Harrison and a few other people involved – like the designer Brady. Then it became obvious nobody wanted to release the records we were making. Judy Nylon’s still pissed off with me because we couldn’t place her album somewhere. Geoff Travis at Rough Trade liked the New Age Steppers album, so he helped me with P&D. In the end I was so broke I that I was giving records to Cherry Red for less than I was making them for.

Dan gave me that first remix, and I started getting a name for doing these weird versions. From that I decided I was going to start something new, something more experimental, under the banner Dub Syndicate. The first time the name Dub Syndicate appeared anywhere was on the back of the Creation Rebel album, Rebel Vibrations. I’d put “Mixed by the Dub Syndicate” on the credits. I`d do things like that for fun, to make the records look more interesting. You know I`d write “another 1991 production” when it was actually 1981. It probably backfires a bit now. I’d sometimes credit myself as “Crocodile”, because, well, our bass player, Lizard Logan, was Lizard, so I thought, I’ll be crocodile. I’ve always liked crocodiles. You’ll see that they pop up in On-U artwork, posters, and stuff. I’d also put “Rhythm by Prisoner”, because we discovered a lock-in facility on the AMS Delay where you could put in samples. This was before samplers existed. We had up to 10 seconds on the on the machine, and we used to call it “captured sound” – hence “Prisoner” – because we`d capture it and trigger it rather than just flying in things off tape. That`s why those early records are much more interesting than completely accurate grid based productions.

I’d worked with The Fall, who had an almost anti-production approach, and I’d been reading about using studio acoustics, off-mic recording. Dub Syndicate was a home for my own experiments. The Manor studio, for example, had a huge stone room, which really influenced the sound. The first Dub Syndicate album was called The Pounding System: Ambience In Dub. Style’s not on that one, but every time Scottie came to England, he’d stay for maybe a month, and when I had access to him, I started running sessions again.

After the first few Dub Syndicate albums, Style said, “Look, I wanna run some sessions in Jamaica.” So he started recording rhythms there, and bringing them to London. I then overdubbed them, added keys and samples, processed them. This resulted in the first co-production which was Lee Perry`s Time Boom X De Devil Dead. That ended up coming out on EMI. So, unfortunately, at the moment we’ve lost the rights to it.

Stoned Immaculate was a very successful album, and off the back of that Style also started to do gigs under the name Dub Syndicate. We did the albums Echomania and Ital Breakfast, but by then On-U had about 9 people working there, and again I was on the verge of bankruptcy. So at that point, which was about 30 years ago, Scottie started his own label, Lion & Roots, and took over the Dub Syndicate project – and ran brilliantly with it. He toured it over all over America, Europe, Japan, everywhere. Style had a fantastic band.

Style had Scientist mix the album, Mellow & Colly. Nothing to do with me. He also had Steven Stanley – one of the greatest engineers ever – do the single, One In A Billion. You know the Luciano tune. Most of the work was done in Jamaica by this stage, but Scottie would bring the tapes over to me and we’d work on them together. He`d usually stay with me, and he`d also pop out buying stuff like car parts – he had a passion for expensive motors – shipping back things to Jamaica. I think he did 4 or 5 albums, and a few compilations on Lion & Roots. The last album he did, Hard Food, we mixed in my house Ramsgate. He was stood here in this kitchen, cooking. That was just before he went back to Jamaica and was killed.

As the Dub Syndicate line-up stabilised around Style Scott, the band also established its sound. While their vibe over the decades didn’t change, the production undoubtedly became more and more polished. Each Dub Syndicate album has its own, mellow flow – they are all consistently chilled sets – but each new LP is sonically, definitely a continuation of the last. Nothing is designed to be jarring, or radical. They’re promoting peace, perfect peace. The tag line, “Ambience In Dub”, featured on the group’s first release, “Pounding System”, has applied the whole way through their oeuvre. However, each cut is characterised by its own little quirks. So, every album could easily be played from start to finish, as “BGM”, perfect for an immaculately stoned “afters”, but, equally, cherry picked by DJs for the dance.

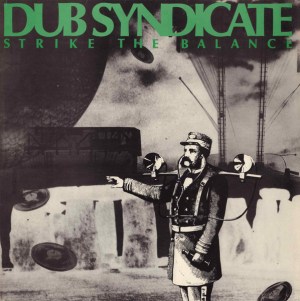

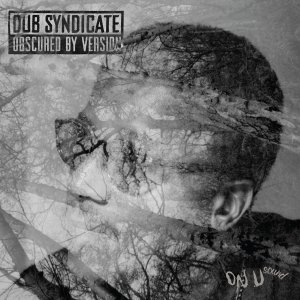

Dub Syndicate’s Out Here On The Perimeter 1989-1996 can be ordered directly from On-U Sound. The package includes the albums Strike The Balance, Stoned Immaculate, Echomania, and Ital Breakfast, all remastered, plus a bonus LP of previously unreleased takes, titled Obscured By Version. As well as the CD and vinyl box sets, I think each disc will also eventually be available individually.

Discover more from Ban Ban Ton Ton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.