Take me out tonight, Because I want to see people, And I want to see lights, Driving in your car, I never, never want to go home… – The Smiths, There Is A Light And It Never Goes Out

Davey keyed the ignition and said, “Stick the tape in.” Sat shotgun, Bobby duly obliged.

“In The City There’s A Thousand things I Wanna Say To You…”

Bobby and Davey weren’t Mods. They didn’t have the uniform: button down shirts, stay press strides, or fishtail parkas. Davey, instead, rocked a big quiff and this massive, vintage sheepskin flight jacket. He wore it everywhere. Whatever the weather. Bobby was a budget Morrissey. Picking bits from Top Man that he thought might pass for Body Map. However, young, perhaps they were mods by default.

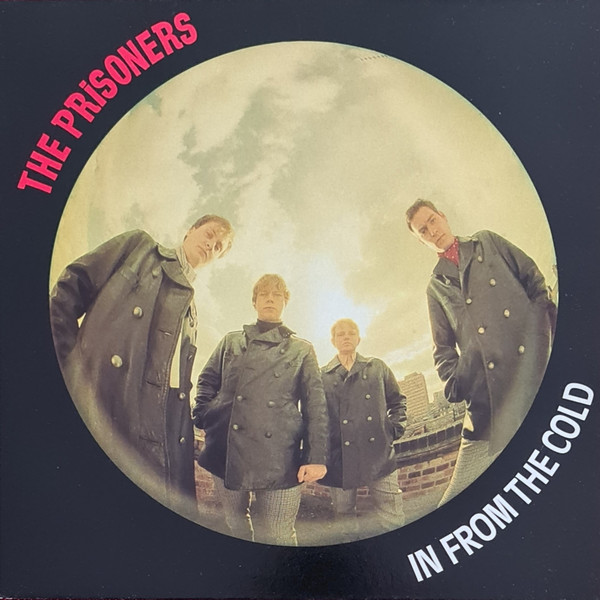

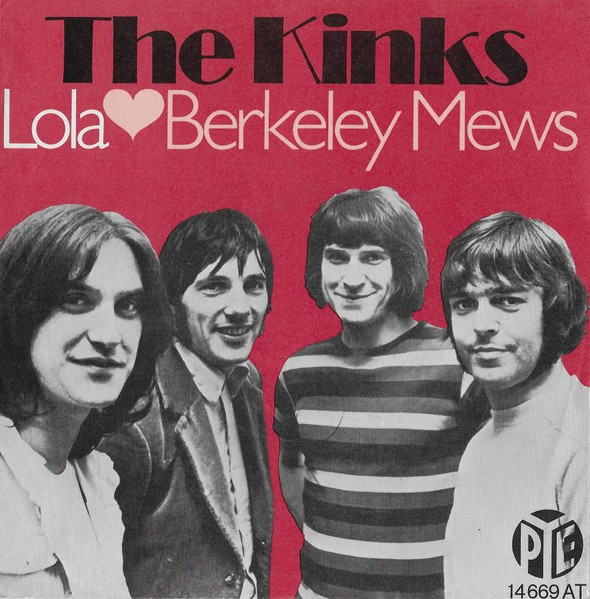

Davey did have LP by an outfit called The Prisoners. Songs that spiralled between the mad, angry, misogynistic, 60s psyche organ grind of “The More That I Teach You” and the hungover self-pity of “Mourn My Health”. He also had a 7 of The Beatles’ “I Saw Her Standing There”. Does that count? It was something the two of them goofed to when girls were in the car. The “woos” and “oohs” increasingly exaggerated. Their off-key harmonies inspired by TV’s “Young Ones”, Rik and Vivian. Turning to face each other, like John and Paul. Shaking their heads in a mock mop top fashion. The Kinks’ “Lola” was another `60s favourite. Davey coming into his own on the “EL-o-EL-o-LoLa” part.

Most of the old songs Bobby and Davey played were things that they used to work up gags and routines, but there were moments, some tunes, like The Who’s “My Generation”, that were 3 minutes of high happiness. Manic confidence. Speeding, fleeting, seconds when, whoever was in the car, it felt like a gang. The boys and girls all stuttering, “Why don’t you all f-f-f-f-f-fade away.” Never for an instant, bothering to imagine that this wouldn’t last. Keith Moon’s drums crashing. Roger Daltrey’s sulphate-driven tambourine. “Substitute”’s angst set to music the pair’s teenage need to be on the outside.

“The simple things you see are all complicated…”

Different.

“Quadrophenia” was something they’d watched over and over, and copped a ton of attitude from. Boys and girls, both, associated with Jimmy and Steph. While set in the `60s, the film’s working class lives still mirrored Bobby’s, Davey’s and those of the girls they were chasing. Dead end jobs and weekend flirts. Plus they all dug The Jam.

Bobby’s girl, cutting, and super sarcastic, to quote The Jam’s “Start”, loved “with a passion called hate.” The bulk of the 60s stuff that Bobby taped was in an effort to impress her. Cassettes constructed from cuts culled from compilation albums and second-hand 7s. Her parents had been proper mods, her dad still had a cool 45 collection, and the way she dressed vamped on Biba and Mary Quant. Straight lines and monochrome. Blonde bob with not a hair out of place.

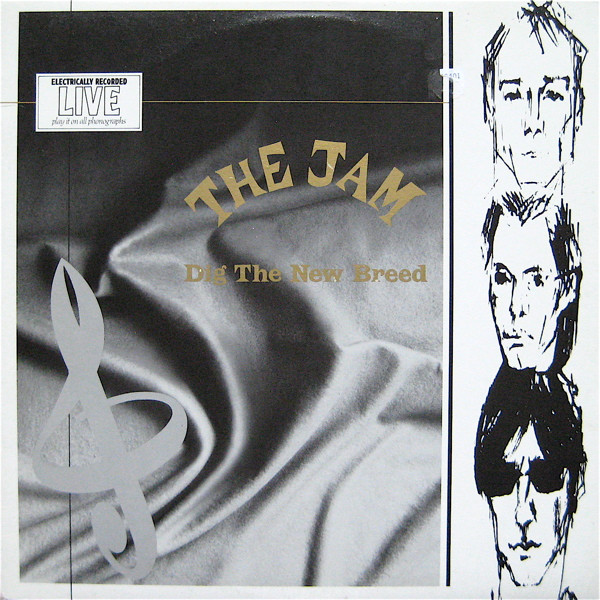

“In The City”…, the live version on “Dig The New Breed”, begins with Paul Weller muttering, “Here’s a tune you might know”, before it races out of control, and Bobby and Davey would jump around, with this blaring in Davey’s room. Tennis rackets for Rickenbackers. Davey’s bed their stage. The two of them pogoing, throwing furious Weller, via Pete Townsend, windmill shapes. Knees bent low for a short, sharp solo, and then leaping, scissor-kicking, into an imagined adoring, exclusively female crowd.

“We wanna say, we’re gonna tell ya, about the young ideas…”

Idealistic. Incorruptible. Indestructible. Together. True. Sometimes sporting fake Ray-Ban shades.

“Is She Really Going Out With Him?”

Bobby and Davey were a bit too young for punk. They just missed it. In `77, they’d have been 11. The only band from back then they were into was The Jam. Then there’d been this Channel Four documentary, “The Way We Were”, which celebrated Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and his TV arts show called “So It Goes”. Singing his praises, it featured loads of clips of new wave and punk bands that he’d given airtime, between `76 and `78. It gave Bobby and Davey glimpses of performances by Joy Division, Penetration and Iggy Pop. Iggy, totally wired, prancing around shirtless in silver spandex pants, wearing a horse’s tail as he sang “The Passenger”. Bobby videoed the program, and also recorded the songs onto a cassette for Davey’s car. Iggy’s cycling riff would drive them through the night, into chance and possibility. Hook ups, punch ups, blackouts, as they made a break for it.

“Let’s take a ride and see what’s mine…”

Boredom their only enemy.

The Buzzcocks were big for the friends. Bright, brash and sing along, like `60s bubblegum on speed.

“Ever fallen in love with someone you shouldn’t have fallen in love with…”

All the songs they were into, well that Bobby was into, seemed to be about heartbreak. On teenage mission to find a soul mate, Bobby didn’t feel desperate, down or daunted. Only determined. Someone was out there, in Wreckless Eric’s “Whole Wide World”, and it was all about the search.

The duo dug The Damned. Especially “New Rose”, and on cue recited the Shangri-Las intro:

“Is she really going out with him?”

The tribal tom toms beating out another breakneck, sulphate-sniffing love song. This one with a couldn’t give a fuck attitude. Bobby and Davey also felt a strong kinship with Captain Sensible, since he’d gone to their school. They weren’t sure if he was expelled, but that story fit fine with the mythology.

The only proto-punk thing they had was “Louie Louie”. Something they’d heard it in the film, “Animal House”. Bobby then found an “Old Gold” copy of The Kingsmen’s 45 in the second-hand store, Beanos, on Surrey Street Market. Increasing incoherent and slurred – just like John Belushi in the movie – was how they sang it. That led them to things like The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me” which was basically a Kingsmen rip-off. Bobby then met Mick, who was Croydon’s only black psychobilly. 6’ 3”, with a shaved, shaped, mohawk-like barnet, he was always dressed in the same tattered Varsity cardie, with a red kerchief tied around his neck. Sweatbands on his wrists soaked in Tippex thinners.

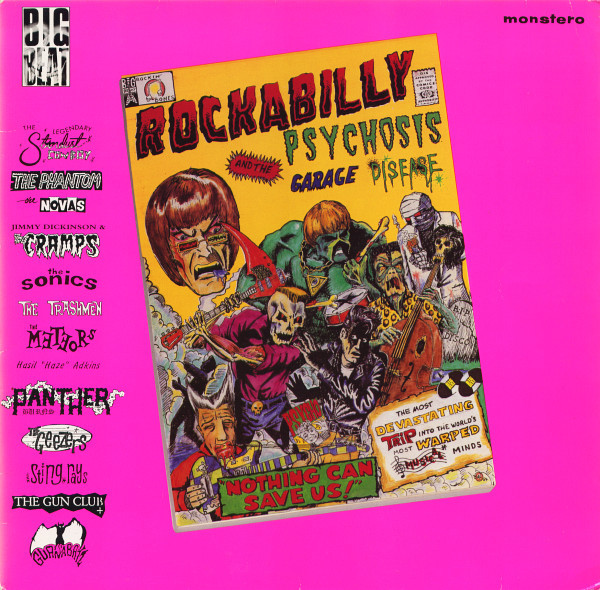

Mick made Bobby tapes with tracks by The Count Five, The Sonics and The Trashmen. Songs cherry-picked from comps with titles like “Nuggets” and “Rockabilly Psychosis & The Garage Disease”. Songs that Bobby and Davey adopted. Deranged, dangerous, off-the-rails rackets, that veered into novelty, but were really rough, raw, noisy and rocking. The Sonics’ “Psycho” was a mad, monolithic mod grind, with funky drum fills, and horny saxophone blasts. R&B like a sex-crazed, more primal Little Richard. Possessed by puberty, it screamed “Wow!” and “Ow!” from the pleasure and the pain. It was the perfect soundtrack for fast, furious fucks. Teenagers tearing the clothes from each other, the act over before the record stops, in an explosion of a pent up energy, that had nowhere else to go. Toilet and alleyway trysts that finished with hastily straightened skirts and fingers quickly rearranging pomaded hair.

Made bolder by Mick, Bobby and Davey headed for The Klubfoot, a rockabilly / psychobilly shindig in Hammersmith. They only went the once. When The Clash “sold out” and made “London Calling” and The Pistols re-emerged as the more experimental Public Image, a lot of punks looked back to rock’n’roll and rockabilly, which then mutated into psychobilly. Ex-skinheads and Confederate flag-waving retro-rednecks made up most of this revival scene. When Bobby stood at the brightly lit Clarendon Ballroom bar, getting the drinks, he happened to catch the crowd in a mirror. The place was heaving. He and Davey were the only folks in there, male or female, with all their teeth, and no tattoos. Instantly his confidence crumbled, and terror, instead, set in. They’d gone to see Restless, fans of their covers of “16 Tons” and “Baby, Please Don’t Go”, but the two of them stood on the dance floor, not quite shaking, too afraid to move.

“The Sun Comes Up, Another Day Begins…”

The bands on Creation Records were pretty easy to see live. Most weekends Bobby and Davey would travel into London for a gig where there’d be 2 or 3 on the bill. Biff Bang Pow, Felt, Primal Scream, The Jesus & Mary Chain. Getting hammered in a university union hall, drinking lager from plastic pint glasses that would spill, crack and collapse as they’d try to make their way through to the show. Between them, Bobby and Davey bought everything on the label, often without having heard it. They were often disappointed, even if the single had been raved about in The NME. Shelling out for shit like Baby Amphetamine.

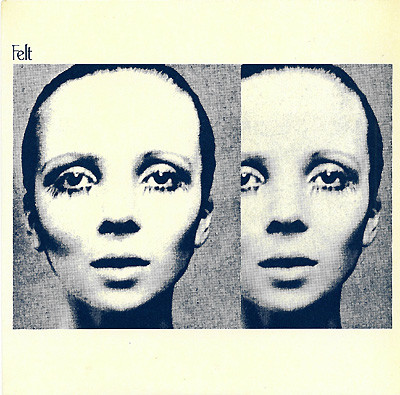

Felt were firm favourites, though. The singer, Laurence, had cool hair and cool clothes, and again there were `60s derived sensibilities. “Penelope Tree” was urgent strummed pop, and Bobby coveted Davey’s copy, not just for the music but also the cover that harked after a past style and glamour. “Down But Not Yet Out”’s undefeated lyric soared a glorious summer swell of 12-string jangle and mod organ. “The Final Resting Of The Ark” spoke of seduction, broken promises and art that they knew nothing about. Its moody late night saxophone skronk a bit like The Waterboys. “Primitive Painters” had this ethereal, hymn-like quality. All its fragile elements building this swirling wall of sound. Like them, Laurence, longed for a life less ordinary. Suffering setbacks, but defiantly determined not to settle into self-doubt. Refusing give up.

The Bodines brought more jangle. Theirs wasn’t elegant though. Instead boisterous, banging, unruly. “Therese” tumbled, tripped over its energetic, enthusiastic, over emotional self. Just as clumsy as Bobby and Davey. Dancing, dizzy like loons. All angular knees and elbows. “Heard It All Now” could have been about jealously, infidelity, insecurities. Spiteful fights. It was something Bobby listened to on the days when his girl refused to come to the phone. “Skanking Queens” was joyful. Four in Davey’s car driving. Heading nowhere in particular. Their lives ahead of them. Carefree. In love. Maybe? For now.

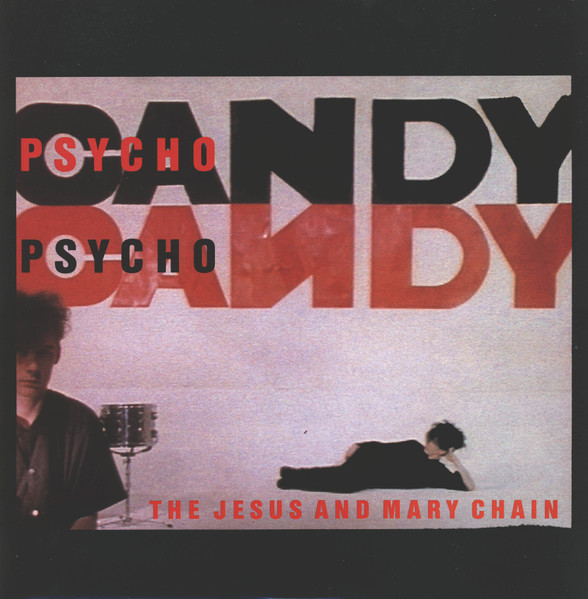

Bobby was jealous of the Reid Brothers, William and Jim. The Jesus & Mary Chain. Together with Primal Scream they seemed part of a big group of friends who were always sharing, showing off cool music. Digging up cult LPs from the `60s and `70s. Dropping artist names and album titles in interviews. Brandishing, clutching rare sleeves. They covered Syd Barrett, Can, and Bo Diddley. Giving a few of their influences away. John Lee Hooker was likely another. “Shake” starting off as a blues, before it becomes a guttural howl. The super radio-unfriendly robotic rockabilly of “Kill Surf City” clearly in love with The Cramps. All Bobby had was Davey. All Davey had was Bobby. No one was sharing this treasure with them. They were having to make do with buying blind, taking chances on what they could find in Croydon’s second-hand shops and bargain bins.

Bobby picked up a copy of “Upside Down”, because he’d read about the riots at the Mary Chain’s gigs in the NME. The inky weekly compared them to the Sex Pistols, a new angry energy, a new revolution – dark, malevolent and violent. Bobby didn’t know much about even The Pistols backe then. Together with the band’s follow up 45, “Never Understand”, it became a call-to-arms when they drank and danced at an indie club called The Underground. An excuse / chance to charge about like headless chickens, lashing out in a crowd of similarly smashed young men.

Davey bought the debut LP, “Psychocandy”. The friends were still in 6th form, studying for A Levels, with only Saturday jobs. Both of them had limited funds, so didn’t duplicate much. Tracks like “The Living End” were a furious filthy amphetamine rush of fury, that drew on The Ramones, The Stooges’ “Raw Power” and “Metallic K.O.” and threw in the odd, Industrial, Einstürzende Neubauten clank. Bobby and Davey didn’t know about any of these references til way later.

The Reid Brothers spewed nihilism, narcissism and self-loathing in equal measure, while shouting about motorbikes and leather boots. It was easy to see how stuff like this might set off a suitably cranked up crowd. The feedback was mind-bending, but not everything was screech-soaked. Bobby and Davey were just as keen on the softly strummed numbers. Songs like “Cut Dead”. Strung out surf. Part Beach Boys. Part Velvet Underground. But even they mixed, equated, love and violence. Where the objects of desire were crazy kittens from exploitation movies and video nasties. The sort of films screened at Scala all-nighters, the cinema in Kings Cross, somewhere, that, sometimes, provided Bobby and Davey with an alternative Saturday night out. Twisted S&M nursery rhymes. Where wired femme fatales ran around with sharpened pointed blades, pissing everybody off. Bobby and Davey pictured people dressed in retro / second-hand `60s chic. Speeding behind sunglasses. Imagined exactly the sort of party that they were never invited to.

Bobby and Davey’d listen to the acoustic versions of William and Jim’s songs, the demos that came as b-sides on 7” double-packs, as they drove late at night. Taking Davey’s battered Ford Escort through Croydon’s deserted, sodium-lit, silent streets. Looking, searching, for a way out. Something about those songs smacked of innocence being lost. Mirrored their own teaming teenage experiences.

“Here She Comes Again, With Vodka In Her Veins…”

“Shambling Band” didn’t sound very complimentary to Bobby, but the indie acts collected on The NME’s C86 cassette, and given this nickname, gigged regularly, and were easy to catch. All of them rotating on the student union circuit. Bobby and Davey weren’t really sure if they liked the music. It was more the press had made them curious. The bands might have been amateurish and their records Lo-Fi, but Bobby and Davey didn’t really care and didn’t know any better. The Mighty Lemon Drops, for instance, could swap The Bunnymen, while the boys were waiting for a new Bunnymen album.

Most of the bands and music shared Creation’s obsession with the `60s, like Primal Scream’s “Velocity Girl”, a tribute to Andy Warhol’s muse, socialite Edie Sedgwick, so to Bobby and Davey was just a continuation of that. They naturally had no idea who Edie was, but The Scream’s druggy, bubblegum nursery rhyme made them despearte to find out. It conjured the exactly the kind of crazy, dangerous, foxy force-of-nature the friends were dreaming about.

Photos on record sleeves and interview quotes were Bobby and Davey’s only clues, sending them looking for old films and books. There was The Scala’s screenings of cult movies, plus Bobby had a part-time job in a library. That was the great thing about all of these records, and the weeklies’ reviews. They would always, in referential fireworks, suggest a search for something else. Booby and Davey sought out Arthur Lee’s Love off the back of Aztec Camera.

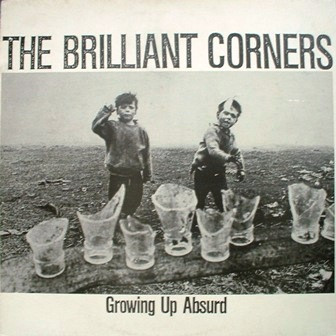

Brilliant Corners’ “Growing Up Absurd”, the brassy swing of The June Brides’ “Every Conversation”, for Bobby they sort of blurred into one. Vaguely political, downtrodden, `80s, dole, kitchen sink dramas.

“Everyone goes where the beer goes…”

Packing punk’s DIY and Velvet Underground’s two chords. The music could stretch to country-fied melancholy. Metro Trinity’s “Spend My Whole Life Loving You”, pedal-steeled, strummed and fiddled had more in common with Martin Stephenson & The Dainties. A poor man’s Prefab Sprout. Mighty Mighty, “Is The Anyone Out There?” and “Throwaway” sounded like The Housemartins. Morrissey raised on Northern Soul. The Razorcuts, “Summer In Your Heart”, “Sorry To Embarrass You” were wilfully lispy, weedy and twee. Bobby and Davey, though, got caught up in the infectious enthusiasm. Folks not far off their age, up on stage, taking a shot at their “15 minutes of fame.”

The thrash of The Primitives’ “Stop Killing Me” clearly wanted to be The Jesus & Mary Chain. Bobby and Davey both had a thing for the singer, Tracey Tracey. “She was looking at me.” “No, she was looking at me.” The Soup Dragons too, took something from The Mary Chain, but they were more like The Buzzcocks. “Hang Ten” was The Beach Boys played at breakneck speed, surf scorched by feedback, but bright, breezy and childlike replaced the Reid brothers darkness. Not some candy talking, instead a sugar rush. Bobby and Davey were once in the middle of a crowd of headless chicken dancing chaps at a Soup Dragons gig, Hammersmith’s arty Riverside Theatre didn’t know what hit ’em, and Davey got K.O.ed. Knocked clean out.

“I’m Gonna Tell Ya How It’s Gonna Be…”

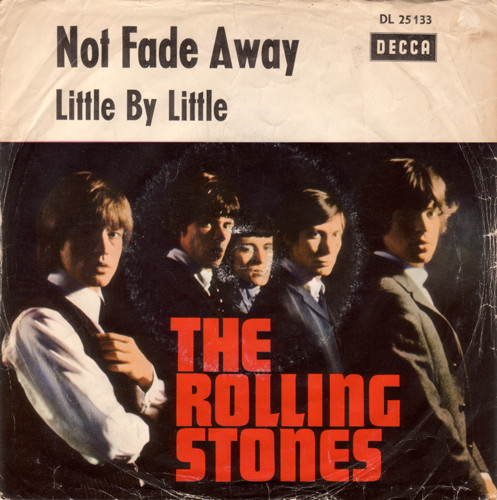

While The Beatles didn’t really get a look in, bar that one tune, Bobby and Davey listened to a fair amount of The Stones. The Liverpudlians’ rivals, in comparison, were rougher, rawer. More threatening for sure.

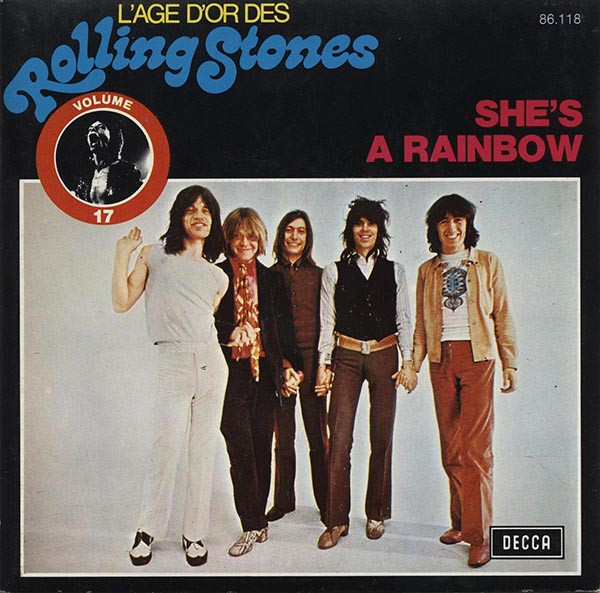

Bobby and Davey sang along with the spiteful, mean, misogyny of the strummed “Play With Fire” and the bullying, boastful, marimba-ed “Under My Thumb”, but the boys also beamed through repeated spins of “She’s A Rainbow”. It’s pretty, prancing piano and strings, a celebration of women, goddesses, everywhere. Bobby and Davey were down on our knees worshipping with this happy, hippie-ish Elizabethan hymn to the female form. They’re hormones in harmony. Their desire to be near its beauty, bathed, bent, by its power, driving everything they did.

“Little Red Rooster” was the soundtrack to steamy windows, and late night fumbling, fooling around. Parked up, in double dates, on deserted lovers lanes, and empty industrial estates. Jagger’s bragging, horny blues, not really matching Bobby’s disastrous virgin fumbling. His inexperienced fingers interrupted by his partner’s laughter, and on occasion, the torches of a couple of curious Old Bill.

Number 1, though, was “Not Fade Away”. The Stones’ first top 10 hit. The band covering Buddy Holly’s Crickets, hijacking Bo Diddley’s “hambone” beat. “I’m gonna tell you how it’s gonna be” hollered the singer, to a frantic strum and a harmonica howl. It was songs like this that sealed a contract between Bobby and Davey. While they span, and while the friends were together, nothing else mattered. It was better than a drug. These were Bobby’s tiny steps toward independence, some kinda confidence. He spent more waking time at Davey’s house than he did at his own. Davey and escape. The two were inseparable.

“And The World Drags Me Down…”

“She Sells Sanctuary” is Bobby and Davey stomping, stamping, anonymous in the crowd, on the the dance floor at The Underground, Croydon’s only indie club. During the week the club would host gigs, but on Saturday night it was an alternative disco.

Davey wouldn’t drive, but Bobby’d meet at his house and they’d drink while they played records and watched videos. “National Lampoon’s Animal House” or “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” would often be on in the background. Davey was a big fan of Dr Frank-N-Furter’s “don’t dream it, be it.”

Otis Day & The Knights’ cover of The Isley Brothers’ “Shout!” was a song that made the tapes. Up until National Lampoon, Bobby and Davey had only known Lulu’s version. It’d come on and, a couple of kids, they’d be clowning, buffooning, twisting. Leaning in for the “sho be do woo be bop” backing. If it came on in a party, just like in the movie they’d limbo down and limbo up for the “a little bit softer now… a little bit louder.” Bobby and Davey even took to catching a revival band, Buddy Curtess & The Grasshoppers, and would join in with the hardcore fans and throw themselves on the floor, wave their arms and legs in the air, when some wannabe John Belushi yelled “Gator!”

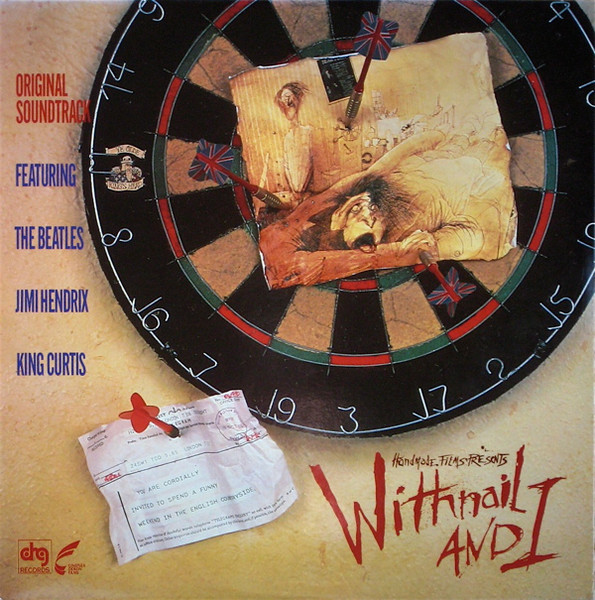

“Withnail & I” was another big movie. A film the friends caught several times at the flicks. The whole thing was quotable. Shit, Bobby and Davey must have learnt the whole script. Camberwell Carrots, fucked clocks, weird thumbs, “honestly, I’ve only had a few ales”, demanding “cake” and “the finest wines known to humanity.” The pair started dressing in second-hand suits, and drinking pints of cider – with ice – in tribute. Who was Withnail? Who was I? Davey would have been the better looking one. Bobby and Davey’d then walk, pub crawl, their way to the club.

They didn’t hit The Underground specifically with the aim of meeting women. It was more about being on the dance floor, legitimately beating the shit out of other young men. Having the shit beat out of them. “Chicken dancing” they called it, lashing out fists clenched, elbows bent. Bobby wasn’t sure if it was because you looked like a chicken, or if you were chicken if you didn’t join in. Flailing with your forearms. It was, generally, good natured fun. With the booze, you certainly felt an exhilaration. A feeling of letting go. Bobby surely had a lot bottled up.

A tune Davey liked would come on and Bobby’d follow him into the fray. There was one time though, when Bobby looked around for Davey, and he turned up under a table. Tongues, hands and legs tangled. The girl was part of the club’s inner circle. Not really goths, but they wore lots of rings, bangles, and big silver jewellery. Attached to the girl’s studded belt were a pair of handcuffs, which Davey assured Bobby she used.

This guy Tim was the inner clique’s leader. He was one of the club’s DJs, and a ringer for Kirk Brandon, the singer from Spear Of Destiny. A look he’d clearly worked hard on. Tim wasn’t physically imposing, but intimidating all the same, since during the day he worked at H.R. Cloake’s the only local independent record shop.

When Davey had gone back to the girl’s flat, a group of them were doing speed at the kitchen table. Bobby and Davey had never dabbled with drugs. They were wary, to the point of being anti. Davey was kind of shocked. Bobby’d had friends who smoked dope, sniffed glue, all sorts of solvents, but he’d never taken part. Bobby was prone to remind you that he was born on the wrong side of the tracks, and Davey would sometimes get his own back. Winding Bobby up with a chorus cribbed from The Spinners: “Life ain’t so easy when you’re a Ghetto Child.”

Bobby too, once, ended up in a shop doorway with someone, after the club had kicked out. She had short curly hair, just like his own, which set her apart from all the hairspray, spikes and mohawks. Sides shaved, the top bouffant like a mushroom. Like a female Terry Hall. Like so many young people in Croydon, trying, wanting, needing, believing themselves to be different. Bobby took her number, but he never called.

Ian Astbury stamping his feet, clapping his hands, shaking his head like a gothic Mick Jagger. Astbury fancied himself as some kind of shaman. A love god. Channeling the power of rock. Beads, scarves and bandanas. A lot of paisley. Bobby’d read an interview where the singer boasted about his “sex energy” and the magic he conjured while beating off. “Hey, hey hey…” and an echoed fragile guitar figure trembled through the ether… then everything exploded. The floor would be still, silent for the intro, then thrashing, singing, shouting. Gasping from the rush. Bobby and Davey’d have what was left of their breath knocked out of them. Lightheaded, spinning, seeing stars, laughing, looking over at one another.

“And the world drags me down…” tapping their anxiety.

“It’s only in her you’ll find sanctuary…” wooing the romantic.

H.R. Cloake’s was intimidating because Bobby and Davey didn’t really know anything about music. They’d spend what money they had based on NME reviews, or names, labels they vaguely recognised and, failing that, interesting covers and sleeves. The young people behind the counter knew this. They’d eye customers from the moment they entered the shop. Spotting any indecision, or lack of confidence. For sport they’d quiz nervous shoppers over whatever they selected. Questions about back catalogue, favourites, whether or not the poor sucker had seen the band live. Looking to expose any ignorance, or better still catch them out lying. It was a sign of Bobby and Davey’s commitment that it didn’t stop them coming back.

“Electricity Comes From Other Planets…”

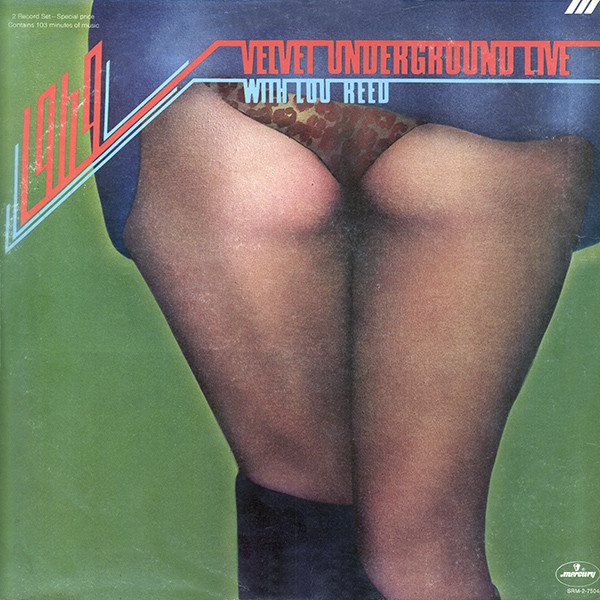

It was a TV arts programme, The South Bank Show, that introduced Bobby and Davey to The Velvet Underground. After seeing the band in their uniform of shades, striped tops, pointed boots and black leather, the indie scene made a lot more sense. The whole thing seemed to have been lifted from Andy Warhol’s silver foil factory. This was what they worshiped and aspired to. The broadcast coincided with the re-release of all the band’s LPs.

Davey bought a copy of the live, double album, the one with the woman’s bum on the front, and he was quite partial to a late night spin of “Heroin”.

“I don’t know just where I’m going…”

It was a rare glimpse of the angst that he usually kept so well hidden. The stuff Bobby wore on his sleeve.

“But I’m goin’ to try for the kingdom if I can…”

Ringing drones, rising and falling between rushes. Lou Reed’s rudimentary riffing. John Cale’s viola screeching, an influence on The Mary Chain’s feedback. Even lighter indie stuff, like The Weather Prophets’ “Almost Prayed”, was basically a romantic rewrite of “Waiting For The Man”.

For Bobby, it was all about “Temptation”, a frantic conga’d, bongo’d outtake, a two-chord twang, that featured ad libs and studio banter, and which closed the TV documentary. A playful, Bobby and Davey would learn, totally uncharacteristic dance number, that nodded toward Motown, shouted to Martha & The Vandellas. Summoned hedonistic scenes of a party stoned groupies in the recording booth.

“If you’re gonna try to make it right, you’re surely gonna end up wrong…”

could have been a motto for the friends’ misadventures. Naive, innocent, amateurly executed plans. The fun they had, by accident, during disastrous, failed attempts.

“Sweet Jane” was a favourite the boys both shared. Learning more about Lou Reed, his deep rooted love / hatred of Bob Dylan, they might have guessed it was a piss-take. With its folky strum and salute to “all you protest kids…”. But turtle necks, berets, beatniks, beat poets, were all new to Bobby and Davey. They took the hippyish positivity at face value. Standing on the corner, suitcases in their hands. They were discovering these things, everything, together, and, fuck, it was formative. Bobby thought about that film “The Dead Poets Society”, and Davey would have definitely been Nuwanda. He might have never read a poem, but he could have honked a mean sax.

“I Know I Was Wrong When I Said It Was True…”

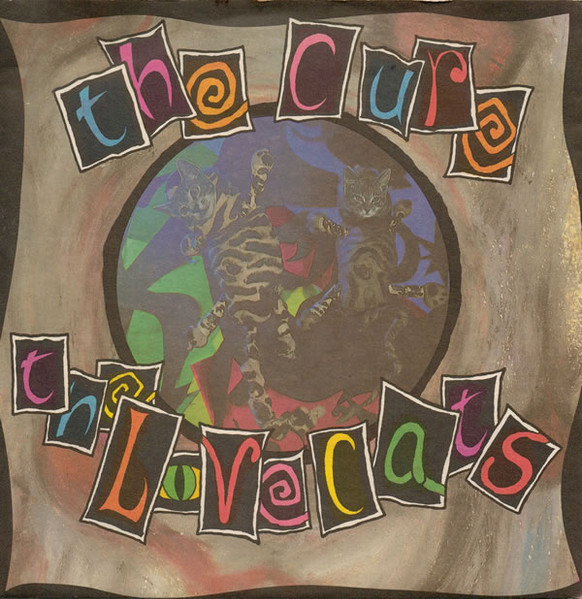

The Cure always seemed to be playing on sunny days. The two, sometimes, often four of them driving. Only Davey, the driver, would know where they were going. Singing along to “Boys Don’t Cry” and its jaunty jangle. The song’s heartbreak way off on all their horizons. Never a reality. Singing along to simple sad love songs that Robert Smith set skipping. Together for “flicker, flicker, flicker…”, “cater, cater, cater, caterpillar girl” and his off-key high notes. In harmony for the hand claps on “Close To Me”, for the whole of “Head On The Door”. Breathless, bitter sweet pop, Bobby had no memory of the bitter now. None of the teenage self-doubt, and “why don’t nice girls like me” insecurity. The anticipation, the excitement, the fear of fucking things up. “I’ve waited hours for this, I’ve made myself so sick…” The insecure shit that Davey would kick him for.

They’d be dancing, bopping, badly but extravagantly. Playing it totally straight-faced in the middle of the floor. Their dates on the side-lines, sucking on a cocktail straw, laughing. Embarrassed, and then past the point of embarrassed. Giving in to the gag. It took real concentration to try to appear that carefree. Ignore everyone watching. Davey made it look like it came naturally. Like he was born to it. They’d clutch their drinks and handbags, scream if the boys reached for them, and refuse to join in. Bobby and Davey, though, they’d have to commit, and keep going until the song ended, and then when it finished act as if nothing had happened. Drop into some comedy macho conversation.

“Lovecats”, a whispering, soft shoe shuffle, was the score for any double date’s conspiratorial air. Forefingers to lips, on tip-toes through midnight’s doorstepped milk bottles. For the bond not just between Bobby and Davey, but also the girls, as they snuck around, doing stuff they weren’t supposed to. “Hand in hand is the only way to land…” Dressed in sombreros and silly outfits. Now knowing Smith, these songs were his drug highs, Bobby supposed. “I love you, let’s go…” “Solid gone.” Albums like “Pornography” his lows.

“In Between Days”, grasped for the giddy rush of life, of love. The ties you form, that you never, ever, talk about when you’re young. The experiences coming too quickly for you to make sense of them. That rollercoaster ride pop stars sing about.

“Move A Little Closer, Ride The Rollercoaster…”

The Bunnymen, the album “Ocean Rain”, and the songs on it, were really from an earlier time. They belonged to a moment a little while earlier when Bobby and Davey had been part of larger gang. Only “Seven Seas”, which was kind of like The Bunnymen doing The Cure – all playful, nonsense, Edward Lear-like, rhymes – was a staple of the cassettes in Davey’s car.

“Stab a sorry heart with your favourite finger…”

“Kissing the tortoise shell…”

But there were other Bunnymen things too. B-sides and live versions. “Do It Clean”, “I’ve got a handful of this…” was punky and angry. It must have been about drugs, but Bobby’s girl insisted it was about sex. The singer, McCulloch, does jump into some James Brown, and it sure stinks of darker desires, I guess. The total surrender to and derangement by them. Vamping on The Beatles, and dream-like drifting into Nat King Cole’s “When I Fall In Love” having grasped, grabbed that handful. Perhaps post-coital.

“Villiers Terrace”, recorded acoustic at Liverpool Cathedral, too, seemed to Bobby to be clearly about stumbling into some squat / shooting gallery. A folk dirge, a warning – “mixing up the medicine…” – Mac now slipping into mock-ney Mick Jagger cockney – “Daze for days…” – dissing The Reds, calling them a bunch of turds, and free-forming between Bill Shankly and Haile Selassie.

Bobby and Davey dug The Bunnymen’s covers of The Doors and The Stones and hammered the band’s new album, which had just been released. That one was their own. Opening with “The Game” and boasting “Pride and proud refusal, I refuse to meet your approval…” Paraphrasing Dickens – “it’s a better thing that we do now…” – staking out righteous revolution. Its puns and wordplay barely pausing for breath, and Bobby and Davey learnt those lyrics by heart.

Davey was into “Rollercoaster”. Careering, careening with a velocity to match the ride of its title, its chorus shouted, screamed like a dare. Had Davey jerking like a skinny Iggy. A horny pony with absolutely nothing to lose. But “All My Life” and its “Oh, how the times have changed us… The line, “Listen, tin soldiers, playing our tune…” seemed to circle back to The Jam. Like a sad reprise. Since the friends were no longer quite that band’s “as thick as thieves.” That part of the adventure, where “everything revolves around laughter and crying…”, burning out. When Bobby packed his bags for Uni – like the final scene where I leaves, and Withnail’s left doing “Hamlet” – Davey got a job in bank.

“I’m Sad To Say I Must Be On My Way…”

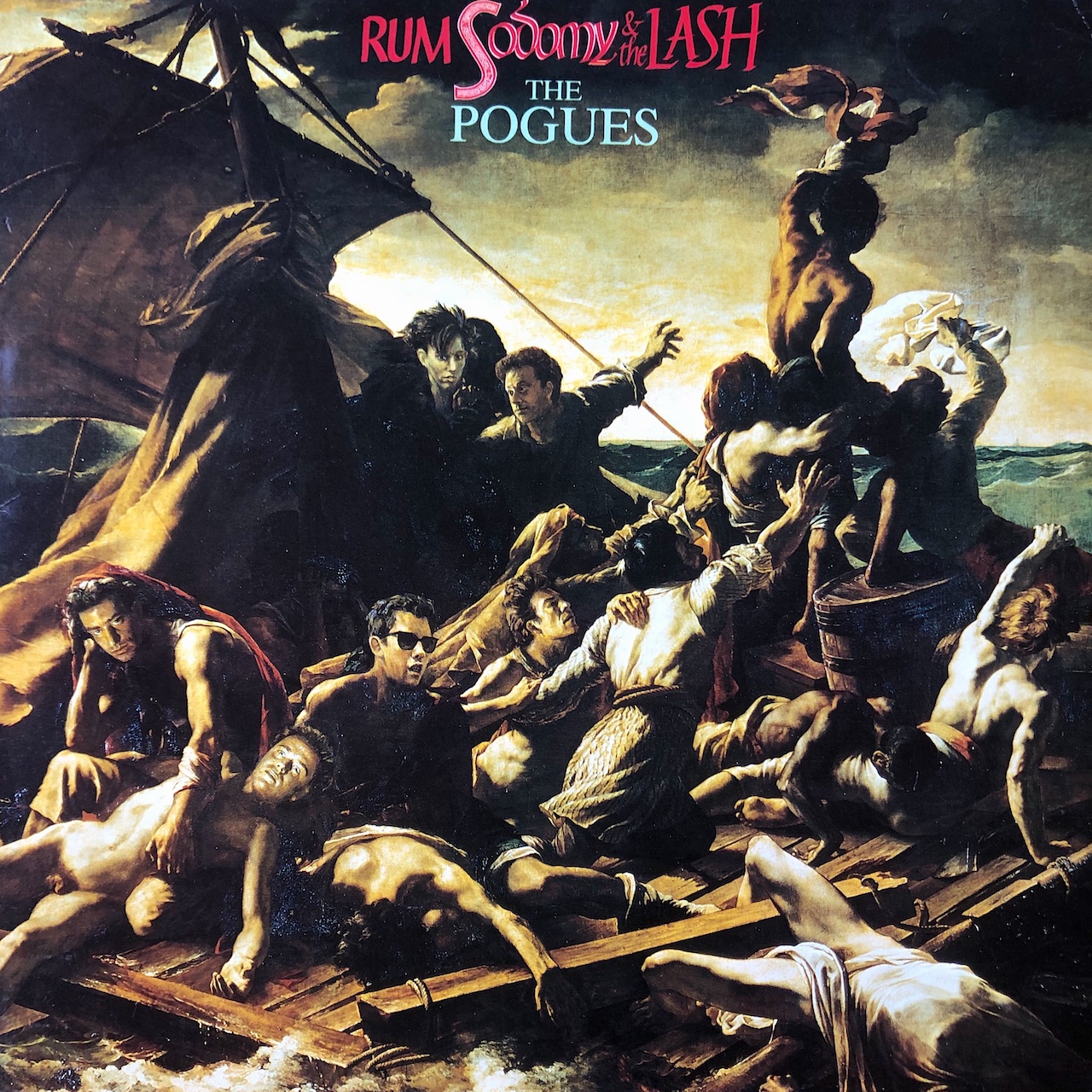

“Rum, Sodomy & The Lash” was a fine collection of mad jaunty jigs, whose lyrics were like another dare, to drink til you dropped. A masochistic, machismo, full of self-destructive bravado. A head first dive into booze-fuelled blackout.

For all the spinning, dancing, forgetting your cares, the darkness was always there. The ghosts rattling at the door, and the Devil in the chair. All the sins of the world – inequality, poverty, racism, war – were recounted at speed as the boys reeled. Bopping to bashed bodhran, giddy accordion and penny whistles. “Singing songs of liberty for blacks and paks and jocks…”

When “Sally MacLennane” spun, one of the friends, Bobby or Davey, would sing Shane’s chorus and the other would imitate Spider Stacey and shout “Far away!” On the dance floor they’d link arms and turn faster and faster. Reckless, taking pleasure in terrifying each other. To bottle out, if either let go, would end in disaster. Both would be flung across the room.

“And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda”, “The Old Main Drag”, Shane always sang his poetry like he meant it, like he lived it, alongside its protagonists. The Pogues’ cover of Ewan MacColl’s “Dirty Old Town”, Bobby and Davey dreamed that dream too, of finding love and burning all the shit they saw down.

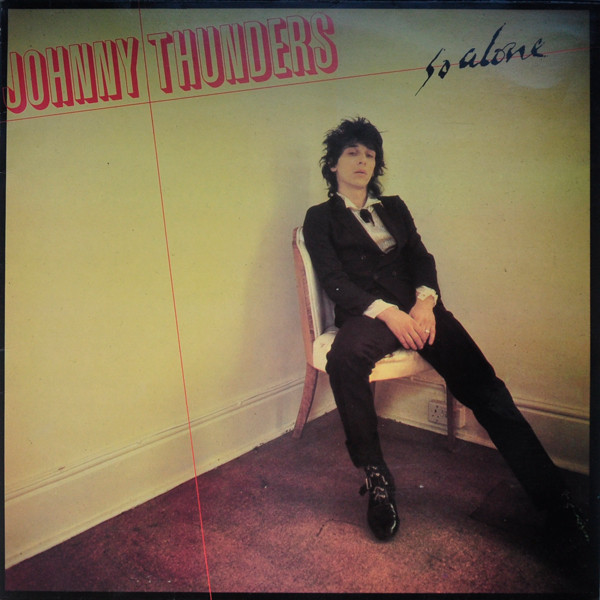

“Haunted” was different, and harked back to The Pogues’ punk roots. The Shangri-Las via The New York Dolls, Johnny Thunders.

“Haunted by the ghost of your precious love…”

Surely a vamp on “You Can’t Put Your Arms Around A Memory”. A simple pop song, it rang with distorted guitars, a wannabe Phil Spector wall. Tinny, but still epic.

Penned for the score of Alex Cox’s tragic Sid Vicious biopic, Bobby and Davey rolled up at some small West End cinema for an opening screening, and somehow were mistaken for VIPs. Taken to a hospitality bar, the pair were given free drinks and got to see the film for free. Legging it, falling and laughing, as soon as the closing credits started, for fear of being found out. Sparked by scenes in the movie, they began weekend drinking in Soho pubs, like The Spice Of Life, in buckled bike boots and winkle pickers, where all the punk bands once got leathered.

Davey’d do this thing where he’d dance with some unsuspecting girl, a stranger, and suddenly, without warning, drop her down into an exaggerated, romantic, Rhett & Scarlett, “Gone with The Wind”, Hollywood swoon. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t, but it always got a scream of surprise and usually a giggle.

There was this one time, though, when Davey came to stay with Bobby at Uni, where he went for this gag, at a student ball. Dressed in a rented tuxedo, clip on bow tie and cummerbund – and as he pulled his victim back up for a potential clinch they both toppled over and the poor girl chipped her teeth on a chair. Only moments before the boys had been dancing to “Sally”. Hammered, singing “I’m sad to say I must be on me way…”, and both instantly sobered up.

Bobby quickly came to hate those balls, unable to shift the working class chip on his shoulder, but this was one was within the opening months of term. When no one knew anybody and everyone was pretending to be somebody else. All the girls he met had made their own dresses. A couple of the guys though owned their own tux. Bobby got bought one for his 21st. He’d asked for an electric guitar. The suit went straight to charity. During the same visit Bobby and Davey had gone to a house party, and Davey’d disappeared. Only to return wearing all the clothes from the washing line.

“I Guess My Race Is Run…”

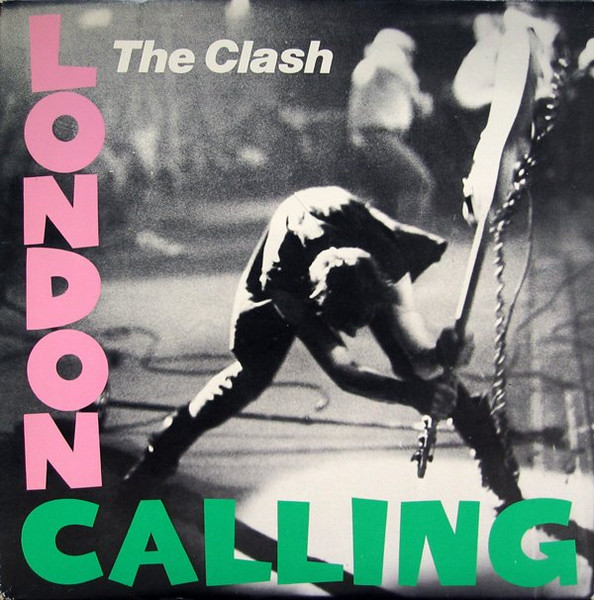

The Clash were a constant on those cassettes. While Bobby and Davey were a bit too young to have been punks, they’d jumped around in drunken abandon at indie discos to stuff like “Should I Stay Or Should I Go”. Trawling through bargain bins they’d each bought what they could of the band’s back catalogue, landing on and latching onto “London Calling”. Bobby and Davey didn’t know that at the time the album had been branded a mainstream rock sellout. Joe Strummer trawling his `50s 45s for inspiration – Vince Taylor’s “Brand New Cadillac” and the legend of Stagger Lee – while Mick Jones indulged his guitar hero fantasies. Both of the boys played the record from beginning to end, over and over, and preferred it to The Clash’s proper punk debut… With the exception of the cover of The Bobby Fuller Four’s “I Fought The Law”, which had been tacked onto Bobby’s copy. That rush as its drum and guitar come thundering in.

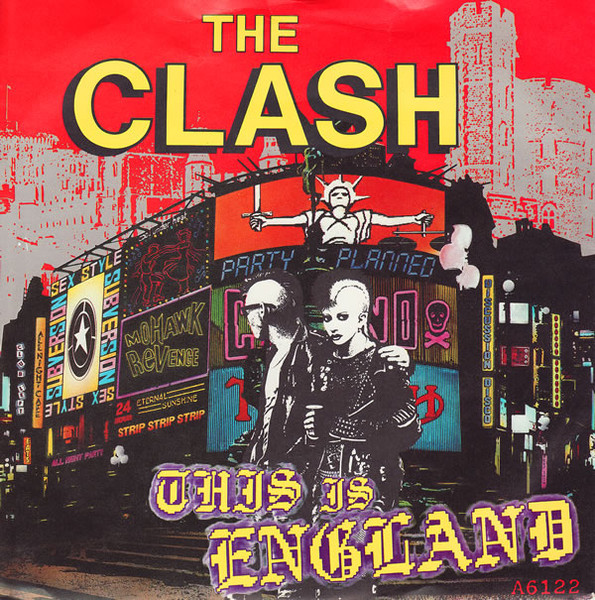

The friends sang along to everything, from “Lost In The Supermarket” to “Rudie Can’t Fail”. Got hooked on the album, “Death Or Glory”’s “He who fucks nuns will later join the church” outlaw / outsider mentality. The title track set their surroundings, dystopian dead-ends, to a great groove, and Bobby didn’t know about Davey – they never discussed that kind of thing – but for Bobby it tapped into, encouraged this kind of nihilism he was developing, where nothing mattered, so you might as well try everything. Something that Strummer reprised, all be it more beaten, a few years later, on “This Is England”. A fuzzboxed, football chanted, drum machine-driven anti-authority of any kind polemic on the sad state of the nation.

“Train In Vain” was an unlisted secret, slipped onto “London Calling”’s last side. Hidden away, perhaps, because it was a traditional, sing along, a love song, and didn’t fit with the band’s political stance. Bobby was already thinking, believing that love would always let him down. Something he knew his friend would never do. Singing it seemed to cement their camaraderie.

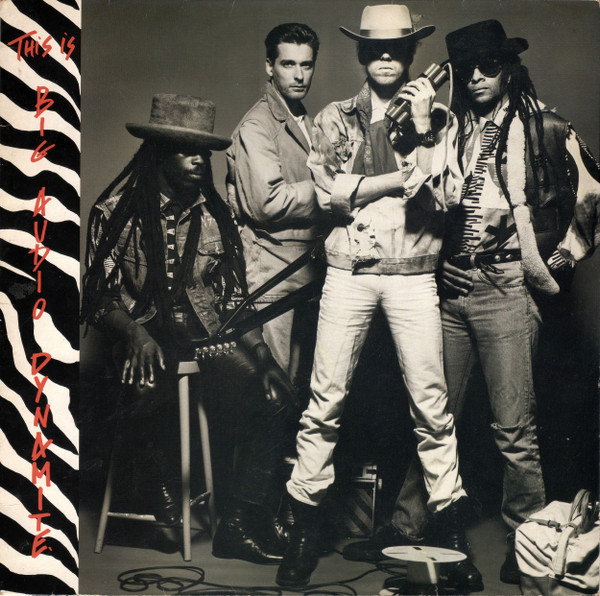

“Medicine Show”, by Jones’ Big Audio Dynamite, mythologised their journey. Made it all the more cinematic with a sprinkling of cool spaghetti western samples. Bobby’d been obsessed with those films when he was a kid. The friends had been in their fair share of scrapes. Been “tarred and feathered”, and chased out of town. Publicly humiliated, screamed at, shouted out, had more than a few drinks thrown in their face. Narrowly avoided beatings from boyfriends. Young and indestructible, Bobby and Davey laughed as they made their getaway.

“Duck, you suckers.”

“Are You Gonna Take This Crap…”

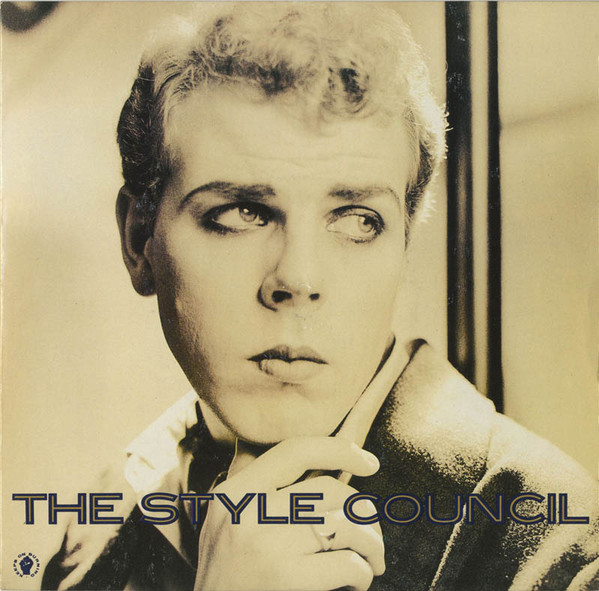

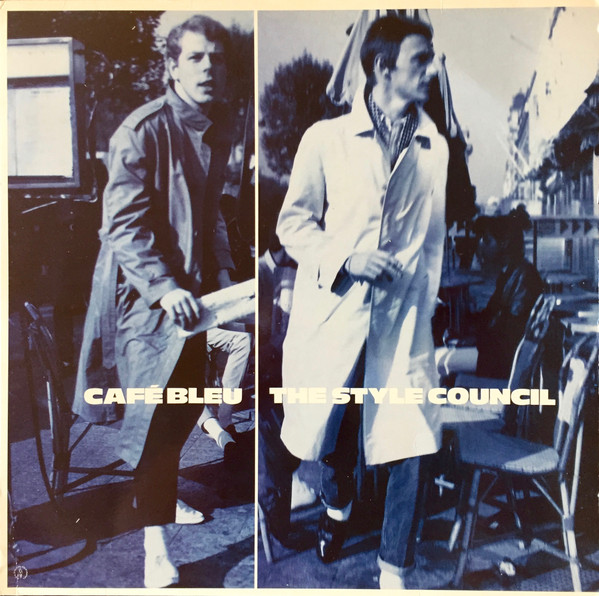

Paul Weller was a role model. Outspoken. Politically active. The sharp front edge of 80s Labour’s Red Wedge. Powerfully positive, without resorting to saccharine platitudes. Often outlining topical problems in his songs. The Jam were mods, 100%, no doubt. The Style Council were still sharply dressed but swapped the punk R&B for orchestrated soul, and jazz, The Small Faces for Curtis Mayfield, and flirted with an art-ier European look. “Internationalists”, not narrow minded British bulldogs.

“Dig The New Breed” was the title of The Jam’s last LP, and Weller, and his council, provided a bridge from the past to a future that aspired to broader horizons. Liking them was a no brainer. Bobby and Davey just grew up with the band.

“Headstart For Happiness” was the friends’ soundtrack to sunny, carefree summer holidays. An acoustic strum, finger snaps and Wurlitzer whirls. It was a love song, really – “When I found you waiting I was old…” – about how people, strangers who become friends, can suddenly, completely change your life, but its sing along sweetness also carried the understanding that these things don’t last.

“You’ve got to leave when your heart says so…”

Everything changes. Bobby and Davey were driving around, knowing that it would be different come autumn. Bobby’d be packing his bags for Uni, and Davey’d be starting that job in the bank.

“Paris Match”, a slow, sad bedsit bossa nova played to Bobby’s unrequited romantic – “The gift you gave is desire…” – but “My Ever Changing Moods” was probably his favourite. The solo piano version where Weller wrestles with his frustration at the world’s injustices, tabloid headlines – “those who promote the confusion…” – and society’s apathy.

“I wish we’d wake up one day…”

Bobby didn’t know if Davey held much truck with the introspective, lovey dovey numbers, but he’d sing “Walls Come Tumbling Down” at Bobby, word for word, while at the wheel. Flicking two fingers to those in authority and pointing at Bobby like a preacher up on stage, asking, demanding to know, if he was gonna take this crap.

“Are you gonna try to make this work, or spend your days down in the dirt?”

Punching out its defiant Motown call for unity. Intent on if not cracking, then bucking, a failing system.

“Shout Top The Top” was the whole car, girls and boys, all underdogs, belting out its glorious chorus. It was impossible not to be taken by Weller’s fire. A working class hero with head and heart fixed on convincing the country’s dead-end kids that they were alright, Weller was a man incensed, driven near insane by inane tabloid headlines, and public ignorance and apathy. Practically on his knees testifying, pleading, begging for revolution and resistance. With orchestral strings and racing piano, set to a northern soul tempo, to say “Shout To The Top” is stirring is a serious understatement. It was a call, a secular prayer, of encouragement to and for the disaffected youth of Thatcher’s Britain. A repeat-until-you’re-hoarse hymn to “don’t fucking give up.” The sleeve featured photographs of hip young things leaping what look like Parisian steps. The camera capturing them in mid-flight. Cool, clipped, positive, left-leaning prose from the “Cappuccino Kid” printed on the reverse.

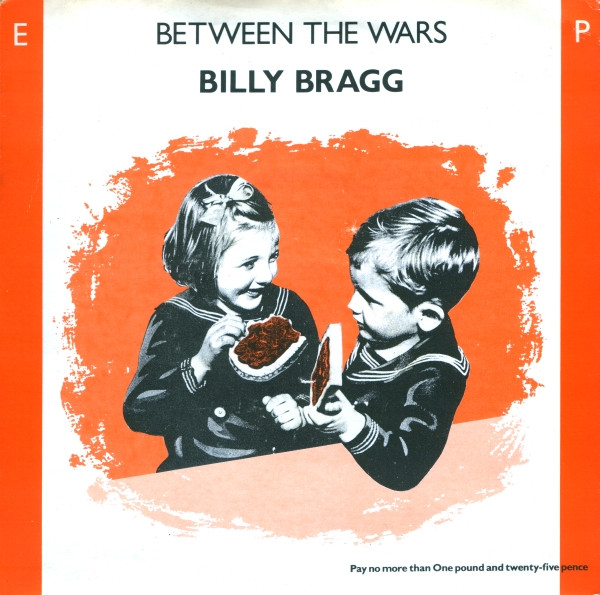

Bobby didn’t know what the girls thought about the music, and Davey clearly didn’t care. The girls rarely commented. They almost never said, “Oh no, not this one again”, although they did once complain about Billy Bragg. They can’t have been in awe ’cos Bobby and Davey weren’t cool. Not by any stretch.

“I Saw Two Shooting Stars Last Night…”

Bobby and Davey were “right on”, but as committed to any cause as The Young One’s Rik. All mouth and no trousers. Joining in with Billy Bragg as he sang about the things they saw and the things they experienced. The everyday, inequality, bigotry, insanity. Racist police brutality. Billy also romanticised unrequited loves in the same 6th form poetry that Bobby did. On “New England” Billy rhymed “I put you on a pedestal…” with “They put you on the pill…”, and Davey was once seeing a girl from “The Roundshaw”, a local problem, “sink” estate who’d been on TriNovem since she was 13. Billy also said he didn’t want to change the world. But he did. And so did Bobby and Davey.

They sang along to “World Turned Upside”, a song about The Diggers, 17th Century socialists, but they never spoke about politics. They really should have been on CND marches, instead of busy chasing skirt. Hearts in the right place. Minds in their pants. Billy went on breakfast TV and belted out “It Says Here”, his takedown of the tabloids, unflinching as he barked the line “bingo and tits…” over big ringing, raucous, chords copped from Marc Bolan’s boogie and Faces records. He dressed like a cliched donkey-jacketed, monkey-booted seller of The Socialist Worker, and would to busk with an amp and speaker strapped to his back. Davey was partial to “The Warmest Room”, a horny rush of a love song. “Here she comes again…” sitting on his hands, biting his lip, waiting. “Lovers Town Revisted”’s “fighting in the dancehalls happens anyway…” was a Friday, Saturday night given.

Discover more from Ban Ban Ton Ton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.