A word from Out Of The Blue, Reminds me how much I once needed you… – Everything But The Girl, Another Bridge

“Did I Dream You Dreamed About Me…”

4AD didn’t feature much on the cassettes made for Davey’s car. Bobby bought a copy of This Mortal Coil’s “Song To The Siren”. Possibly based on an NME review. Probably based on the cover. It could have been that there wasn’t anything new, anything Bobby didn’t already have in H.R. Cloakes’ limited indie racks. It was Tim who sold it to him. It was a record that, when Bobby and Davey first heard it, stopped them in their tracks. There were 3 of them, Bobby, Davey and another mate, Matt, and they all fell silent. No one spoke until it finished. And then they were stumbling for words, trying to change the subject. What it stirred was personal and profound. Something that, young, they didn’t understand and couldn’t articulate.

The chimes, the solitary, icy chimes.

For Bobby it was a deep sadness. A sense of longing for something that would always be out of reach. Bobby didn’t know where he was going, and often felt alone. He didn’t know if anything else was possible. He tried not to think. Hope, generally, kept Bobby fixed on the horizon. But the song made him feel like he was staring into forever. Into hopelessness. Giving him a glimpse of a mission he was doomed to fail, before he’d even begun. Something, a chase, he was committed to all the same.

“Here I am… hear me sing…”

To be noticed. By anyone. Bobby didn’t see some idealised lover, maybe a string of them. A lonely journey. A prophecy. What Bobby saw was the future. Left speechless. In awe of its frightening, terrifying beauty. Besotted by the voice, Davey had quickly tried to find a picture of Liz Fraser.

Despite “Song To The Siren” and singer Liz Fraser’s backing on Felt’s “Primitive Painters”, the friends had never cottoned onto the Cocteau Twins. The NME raved about A.R. Kane, and “When You’re Sad” sounded a bit like The Jesus & Mary Chain. Drum machines, bubblegum pop and feedback. Bass strings twanging out a rigid funk. Clash-like riffs, buzzing, sharp, cut short over nursery rhyme S&M lyrics.

“The hair on your neck forms a noose around mine…”

All very “Taste Of Cindy”, “Psychocandy”, and those noisy guitars were such a rush. “Lolita”, with its sleeve of a naked femme fatale hiding a huge kitchen knife, was an ethereal, echoed, sexy shimmer.

“Hey there winky girl… love to go on down and kiss your curls…”

The fragile fretwork and ballad broken by searing sheets of metal. Someone called it “dream pop” and, Alice In Wonderland-like, it wandered through unconscious obsession, pleasure and pain, prowled the edge of nightmares. Sonically sailing the same waters as “Song To The Siren”. Both AR Kane 12s were produced by The Cocteaus’ Robin Guthrie, but Bobby and Davey weren’t the kind of kids to make that connection.

“We Make A Little History Baby, Every Time You Come Around…”

As the “straight man”, Bobby was supposed to be the miserable one, but it was Davey who went in for a bit of goth. Davey loved Bauhaus’ Marc Bolan cover, “Telegram Sam”, a band Bobby wouldn’t have touched, and Davey would also torture his passengers with self-indulgent dirges by their spin-off, Love And Rockets. “Haunted When The Minutes Drag”, and “Dog End Of A Day Gone By”, its tumbling Burundi drums an echo of The Bunnymen’s “Zimbo”. Lyrically it wasn’t catchy or clever enough to appeal to Bobby. But it wasn’t Bobby driving.

It was Davey who first put Nick Cave on a cassette, after buying a copy of “Kicking Against The Pricks”. The wounded, wild west narrative of “Long Black Veil” was something that stuck. The martyred hero, and sense of honour, struck a chord, though Davey may have been more into the pulling other people’s pussy side to the protagonist.

Davey argued continually, bitterly, with Bobby’s girlfriend – she called Davey a “div” – but it was clear there was a curiosity, an attraction. You know, protesting too much. In many ways they were sort of similar. Blonde and more gregarious. Davey’s girl – who he affectionately nicknamed “Hermie”, because, he said, she looked like Herman Munster – was a quiet brunette. More like Bobby. Bobby had noticed, he didn’t know if anyone else had, and he wasn’t sure what it said about the four of them. If they’d been a little older, more confident, more secure in themselves, or if it had been a few years later, with all the E knocking about, they’d have likely found out.

Once, Bobby was walking home across the railway bridge which cut his street in half. Dividing the poorer terraced bit, from the detached posher. Between the haves and have nots. When Bobby was a kid, part of a gang, they would tear across this thing, daring each other, in a game of “knock-down-ginger”, to ring those big houses’ bells. The Bad Seeds’ “Ship Song” was on his Walkman.

“Come sail your ships around me…”

It must have been midnight. Bobby’s dad would have locked him out, so he was ready for another stint of sleeping in the shed. He didn’t care. His hair was messed up, mad, after kissing his girl’s curls. If not for the first time, then one of the first. Then Davey just happened to drive past, also heading home, in the opposite direction. He stopped, got out, and they both laughed, ’cos his hair was crazy just the same.

“I’ll Try To Love Again, But I Know…”

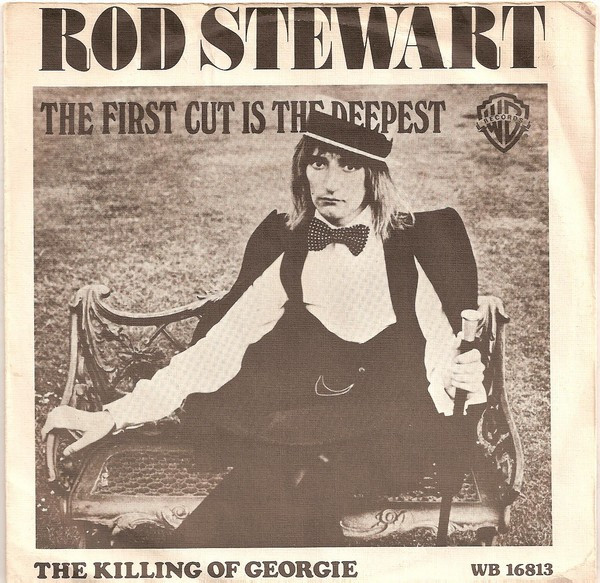

Bobby and Davey would fall into a round of Rod Stewart’s “The First Cut Is The Deepest”, when drunk and walking. Either crawling between pubs, or trying to find parties. Bobby couldn’t remember where the ritual came from, but one of them would kick it off and the other, without hesitation, would join in. They didn’t know all the words. They’d just repeat the little they knew, the same lines, over and over, like a love lorn mantra. Basically the title.

“I would have given you all of my heart,

But there’s someone who’s torn it apart,

Baby, I’ll try to love again, but I know,

The first cut is the deepest…”

The one on backing interjecting, testifying.

“Baby I know.”

More and more extravagantly.

Hey! Guys! Harmonies!

“And she’s taken just all that I have, but if you want I’ll try to love again…”

The opening verse and chorus locked, looped. It could go on for ages. Staggering, singing through Croydon, Norbury and Thornton Heath. Bobby didn’t know if it was Davey’s doing, but he suspected that it was his own.

“New York Says I, New York Says He…”

The album “Don’t Stand Me Down” had Dexys Midnight Runners further cultivating their Celtic Soul Brothers thing, but now, not in inside-out dungarees, but sporting a preppy, yuppie look. The songs that Bobby and Davey listened to regularly were a couple of short spoken word tracks, titled “Reminisce Part One” and “Part Two”.

On “Part One” Dexys were searching for the spirit of Brendan Behan, scouring famous West End boozers, and the bottom of sunk pint glasses. “Part Two” found Kevin Rowland recounting a story of a teenage crush, and centred around the epic Motown melancholy of Jimmy Ruffin’s “I’ll Say Forever My Love”. In the process, Rowland riffed on the chorus of Ruffin’s hit, kinda like Bobby and Davey’s take on Rod… but in tune, and poignant, not pissed. Both were examples of songs that encouraged the two friends to seek out more music, and to go read some books. Lyrics and record sleeves laid out a map of films and movies, authors and novels, that Bobby and Davey assumed they had to consume in order to understand where the artists they liked were coming from.

“Heart’s Like Crazy Paving…”

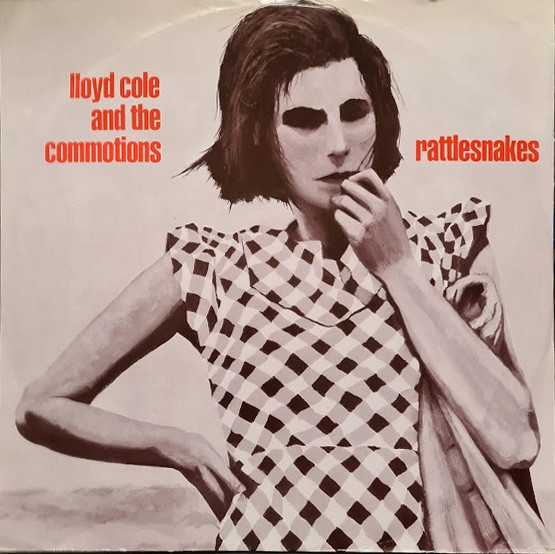

Lloyd Cole loved a literary reference… and Bobby loved him for that. Bobby had a Saturday job in a library, and through lyrics and reviews – Bobby would never have never got all the clues himself – Lloyd introduced him to Simone de Beauvoir, Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, Joan Didion’s “Play It As It Lays”. Eva Marie-Saint, and Marlon Brando in Elia Kazan’s “On The Waterfront”… And by extension, beat poets, benzedrine, amphetamine, Arthur Lee and Love.

Nodding toward Bob Dylan and Lou Reed, Lloyd told tales, painted pictures of protagonists, characters, caught up dangerous emotions, doomed romance. “Rattlesnakes”, raced, string-soaked, “hearts like crazy paving, back to front and upside down”, across Nevada deserts, wide open spaces, a landscape that was pure American noir.

“Forest Fire” was another reckless, romantic, speed-driven spin. “Perfect Skin” dreamed of New York, and “My Bag” was running around it in. Snorting coke. Sinking whiskey and gin. Suffering for its art. Following suit Bobby’d wake up, still in Croydon, choking on vomit. Davey’s favourite, set to countrified gospel backing, “Brand New Friend” reflected on innocence lost.

“When we knew no better it was no crime…”

“Are You Ready To Be Heartbroken?” was all about where the scary journey of adulthood and independence begins. That last summer, “cruising”, it was a warning to Bobby and Davey. Their heads full of optimism and idealism, going out into the world to be kicked, punched and potentially crushed.

“Get Up And Bid The Blues Goodbye…”

Edwyn Collins was having a revival, wearing a big quiff and holding a hollow-bodied semi-acoustic guitar. Initially inspired by The Buzzcocks, Television and Velvet Underground, and then Motown, he reinvented himself as a rock ’n’ roller, leaving the soul boy stuff, just like the Four Tops, behind.

Edwyn released a string of singles, “My Beloved Girl”, “Don’t Shilly Shally” and “50 Shades Of Blue”, that were this kind of tongue-in-cheek bop, Shakespeare, well, Oscar Wilde or Philip Larkin, meets Shakin’ Stevens. He didn’t seem ironic, or cynical. Edwyn sounded like he was having fun, in a way, say, that Lloyd Cole, never could. His whip smart lyrics there to make himself, and his friends, laugh.

Bobby and Davey got hooked on Edwyn’s clever, smart arse wordplay and and hoarded what they could of the singer’s releases. When the pair caught Edwyn live at The Town & Country Club, in Kentish Town, they were part of a huge crowd dressed in stripy tops, Ray Ban shades, and oversized shorts, just like Edwyn’s old Orange Juice photos. They both had their hair shaved brutally at the back and sides, with the top left long, to be either worked into an exaggerated “Elvis” or allowed to flop as a fringe, depending on the gig / occasion.

Music was Bobby’s biggest obsession. His greatest escape. He didn’t think it was quite the same for Davey, since Davey was more balanced. But Davey indulged Bobby, and picked his moments to out do him. Knowing that having something Bobby hadn’t heard would make Bobby even barmier.

“By the time you see things my way, I’ll be halfway down the highway…”

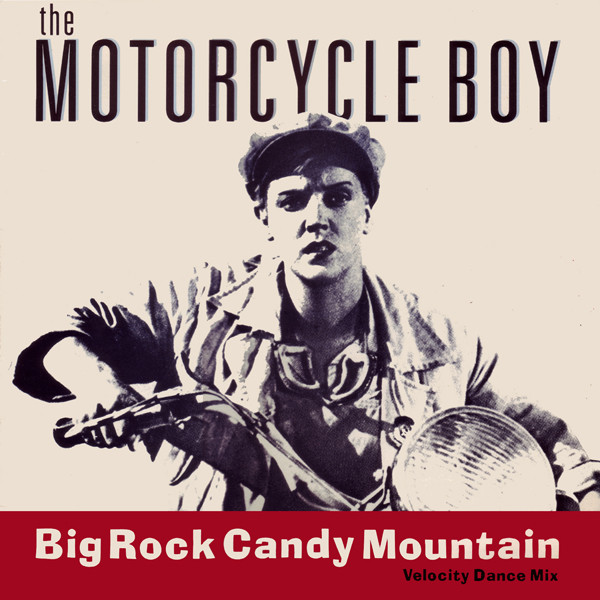

The Motorcycle Boy took their name from Francis Ford Coppola’s “Rumblefish”, the black and white movie where only those titular fish were in Technicolour. From Mickey Rourke’s cool, but doomed hoodlum. Musically they were a bit like The Primitives. As if someone had cashed-in, sold out, and given The Jesus & Mary Chain a pop top 10 polish. Fuzzbox guitars all over a drum machine-driven, retro, bopping, rock ’n’ roll beat. But big, bright and optimistic, not angry, antisocial and sadomasochistic.

“It doesn’t matter what you say, because I’m already on my way…”

“Look for me tomorrow and I’ll be gone…”

“That Was The River, This Is The Sea…”

Bobby couldn’t make it back to the UK for the funeral. He and his youngest were in Tokyo. In from the sticks. In from Nagano’s mountains, where they lived.

The boy had two weeks of university entrance exams to sit. Daigaku Juken. Bobby’d put him up in a small hotel in Roppongi. The kid needed the space. Time alone to focus. It was at the end of a busy street. The furthest from hostess clubs and hustlers that filled the main crossing. The police presence was high. The place was nowhere as bad as it used to be. Bobby remembered 15 years ago, when, walking along you’d be approached with lists of girls. “What are you into? What you looking for?” Every combination of size and race rattled off. He remembered a drug deal with two enormous guys in a tiny elevator. Money on the way up. Gear on the way back down.

From the boy’s hotel you had a nice view of Tokyo Tower. Tourists were posing for photos in the middle of the road, with the monument pinched between their fingers. In the mornings, when Bobby came to pick him up, the place was virtually empty and the pavements being hosed. A couple of the clubs would still have security positioned outside. A few of the girls would catcall. Try to convince Bobby that he had the time. He was flattered that they even noticed him. It gave Bobby a chance to practice his very broken Japanese. Them, their English.

Bobby was staying with his wife, in her apartment in Nishi Azabu, about a thirty minute walk away. They were living separately, but not legally separated. A 25 year marriage now a long distance relationship. Work and logistics had been the excuse. Bobby’d admit he was having difficulty letting go. On the days between the exams, Bobby and the boy would scout the venues. Travel around on the underground system, The Metro. Planning routes and watching journey times. Trying to make sure that there was one less thing to worry about. On the days of the actual tests, Bobby’d drop him off, and then catch up with his older sons, who were also studying in the city. He’d bully them into accompanying him to galleries, museums and movies. Take them out to lunch. For all the people and the bustle, Tokyo can be a very lonely place, and Bobby’d stress about them connecting. All it takes is one bar, one cafe, one restaurant, one friendly face, and you have a way in. But you have to be out there, in amongst it, to find it. Daniel Johnston and his song about true love being “a promise with a catch” played on a loop his head.

At the end of the day, Bobby’d collect his youngest and they’d dissect how he’d done. The kid’d kick himself over silly mistakes and his dad would tell him that everyone in there would have made the odd fuck up, and to concentrate on tomorrow. There’d be time enough for tallying when it was all over. They’d go for dinner with whoever was available, and after taking his son back to his hotel, Bobby’d go drinking with his wife. Bobby’s phone told him that he was walking a total of 20, 000 steps a day.

There was a third floor joint, close to where Bobby’s wife lived, that opened at 9PM, closed at 6. It was somewhere where folks still in need of a drink went to after they’d been somewhere else. Somewhere that stayed serving as long as people were ordering. Before midnight, though, they’d be the only ones in there. Giving them some space to catch up. Kind of like a date, but more scary than exciting. When you know each other too well, and it’s too easy to say the wrong thing and ruin everything. It could go anywhere from here.

The bar had a big TV screen and the bartender would take musical requests. Finding them on Youtube. So on the day of the funeral, given the time difference, at the time of the service, perhaps the very moment that Davey was being cremated, Bobby went to this bar with a list of tunes. He didn’t plan to stay long, but he planned to drink until the list was done. He’d written the songs in order. Each reminded him of his friend.

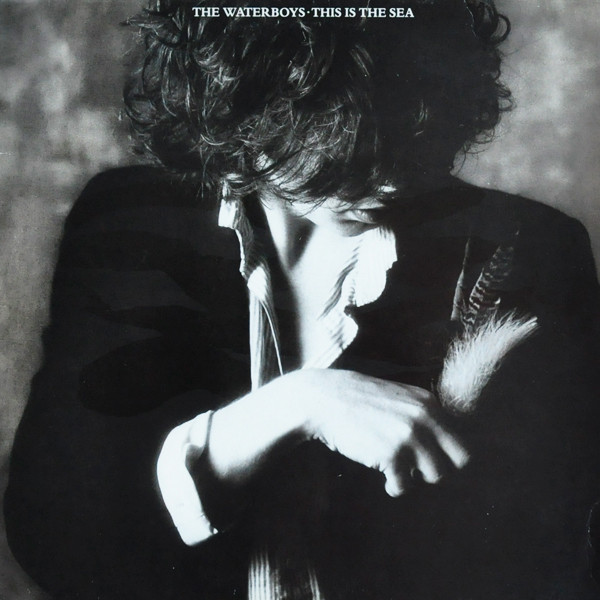

The bartender was up for it, since the room was empty. Bobby didn’t try to explain the tracks’ relevance. He didn’t tell his wife either, and she got increasingly stressed, since it was clear that Bobby wasn’t listening to her stories, as he instead stuck to his tasks: another gin & tonic and the song that was spinning. He soon realised that there was a strong possibility that this would end badly, that he hadn’t really thought it through. He should have come on his own. Baffled, offended and beginning to border on angry, it looked like his wife was going to leave. Then the bartender selected The Waterboys’ “This Is The Sea”, and Bobby broke down, sobbing, freaking them both out.

Davey would play this song, as he Bobby drove around South London in his battered Ford Escort, when the friends were in their teens. Bobby didn’t really get it then. Bobby could do dour with the best of them – shit, “How Soon Is Now?” – but there was nothing poetic or pagan about Thornton Heath. “This Is The Sea” was hippy-ish, progg-y even. A bit Supertramp. It had fiddles. Bobby didn’t really like Dexys Midnight Runners either. He hadn’t heard any Van Morrison yet.

It was a song that they’d listen to late at night. After dropping the girls off. Heading home. The streets deserted. In Bobby’s memory the roads were always slick with rain. It was one of Davey’s tunes, and at the time it struck Bobby as a little bit gloomy. Not at all Davey. He didn’t really do moody. Bobby could only remember a couple of times when Davey was out of sorts. Once, when Bobby had called round at his, he was slumped on a bean bag in his room, in the dark. Bowie`s “Rock N Roll Suicide” blaring.

“Oh no, you’re not alone…”

Davey didn’t appear to do thinking the big picture. If he did, then he kept those thoughts and doubts to himself. He was always here and now. There’s fun to be had in this moment. In any serious, tense situation, in the middle of an argument, he’d pull a funny face, affect a silly voice, come up with some skit and make everyone laugh. Bobby was the straight man. With any comedic duo, though, the dynamic’s a little more complicated than that.

The bartender hadn’t picked Bobby’s songs in order. There were around ten on the list. “This Is The Sea” was supposed to be the last tune. Not the fourth or fifth. Bobby’s wife straight away knew, put her hand on his shoulder, and explained in Japanese what was going on. Bobby felt a bit guilty for laying this on a stranger. Felt selfish for casting a shadow over the guy’s evening and his place of business, but they carried on drinking until all the songs were gone. The bartender hugging Bobby as he left.

When Davey died it knocked Bobby for six. He was in shock for weeks. Crying at least once a day. Bobby balled, howled, when he first found out. Bobby still felt it now in the minutes when he couldn’t keep himself busy. He drove around with CDs full of old music spinning. Knowing it might be torture. Trying, needing, to find those songs that held the most memories. It was The Waterboys who’d made him stop the car.

“Once you were tethered, but now you are free…”

Davey always seemed free to Bobby. More like how Bobby wanted to be. With his friend gone, Bobby didn’t feel free. He felt lost. Davey was the only school friend that he hadn’t left behind in his race to escape where he came from, and the only person who knew Bobby before he started pretending to be somebody else. Before he reinvented himself. Before the self-mythology. Somehow it wouldn’t have been possible without Davey around to burst his bubble. To tell some embarrassing story from their past. “Grounding”, they call it. Without somebody really knowing, somebody else who was there, Bobby could be anybody. Nobody.

Bobby, for the first time in decades, felt terrified and small. Overwhelmed by a vastness. Cast adrift, with no anchor, caught in impossible currents. The song’s climatic, cathartic coda echoed, mirrored, amplified this great rush of grief.

All the stories the pair had shared. A book full of them. All the mistakes and misadventures. Laughter. They`d been too young for real tears. Boy, Bobby was shy back then, but now he was braver, bolder. Davey’s friendship had forced him to be fearless. Bobby hadn’t wanted to let him down. When Bobby got the news he’d been alone in the mountains. His wife, on the phone, worried about him and the bottle said, “Davey wouldn’t want you to hurt yourself.”

“You’re Not Like Anyone I’ve Ever Met…”

Bobby and Davey lost touch when Bobby moved to Japan. Bobby had Davey’s family over just before he left, but, once he was gone, he was gone and rarely returned. It was Bobby’s sister and Davey’s wife who hooked the pair up. The old friends themselves shy of social media. Back in contact, they swapped news of aging parents and growing children, and just like when they were 17, they shared music. Davey would email Bobby mixes. Bobby’d post letters and CDs. Davey was working. Bobby was not.

Bobby didn’t really know why his had to be physical. Perhaps he wanted to emphasise the care he’d put into them. How important the process was. Bobby, the serious one. Something Davey tried, and often, at least momentarily, succeeded in shaking him out of. Davey could always make Bobby laugh, and convince him to do something daft.

To begin with the boys both wracked their brains to remember tunes from way back when. Stuff they’d to drive around to in Davey’s car. It was like piecing together a puzzle, a story. The music, the clues, the cues. Stitching together a soundtrack to a low budget, South London rights of passage movie: A-levels, shit jobs, re-sits, uni and poly. Leaving home, and each other. Larks, loves and heartbreaks. Thick as thieves though, for a few, formative years. For Bobby, when everything was new, Davey was there.

Typically the two of them tired to out do one another. Coming up with classic tunes that instantly ignited memories. Those that scored tall tales and kept secrets. Davey’s “mixes” were kind of random. Made up of Youtube rips. Bobby’s were sequenced by BPM and key. Both of them started to include stolen snippets from films and TV. The Young Ones, Animal House, Withnail & I. The Comic Strip. Mr Jolly Lives Next Door.

Davey made 4. Bobby made 6. Bobby was on a mission. He wasn’t making these things just for Davey. He wanted that music ready in a box, in case of emergency. To have it to listen to, whenever he felt weighed down and lost. Whenever he needed to feel brave and invincible. When he needed reminding of who he was. Bobby and his youngest son would speed down rural highways on the journey to school, test driving these CDs, and they’d only pass mustard if Bobby could picture himself riding shotgun with Davey at the wheel.

Davey wrote back, “You’ve got it wrong”, and Bobby realised his friend was right. Davey’s tunes were Davey’s tunes. Anybody looking over Bobby’s compilations might think they’d been “soul boys”. Bobby’s selections – a lot of them `60s R&B, cherry-picked from Kent and Stax Records collections, Lee Dorsey, Elmore James and John Lee Hooker – were all tangled up with the girl he’d been seeing. The first time he fell in love. Bobby’d also airbrushed out all the cheese. Davey never cared about being cool. Over the decades he’d dig at Bobby for constantly chasing fashion.

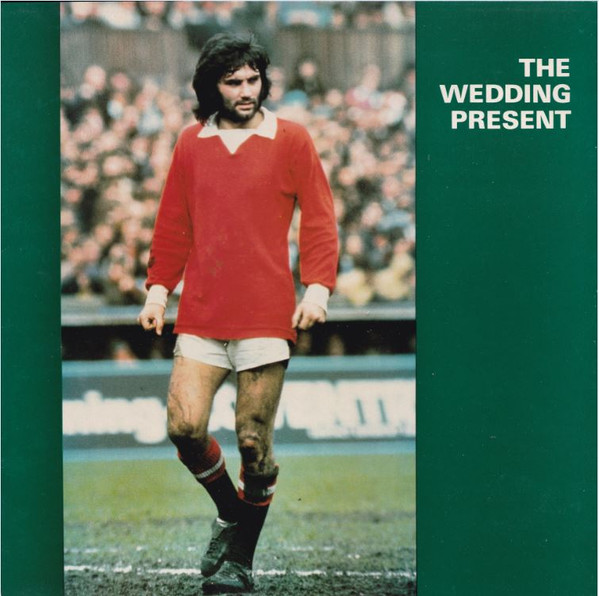

Even when Bobby and Davey agreed on a band, they’d settle for different songs. The Wedding Present were a good example. Punky, romantic pieces with angry, angsty, down to earth, everyday poetry, that Bobby thought he could write, and guitar – a relentless, chaotic, key changing, clipped, barre chord thrash, with no interest or care, too pent up for fancy solos – that both of them fantasised they could play. Bobby, being Bobby, plumped for “My Favourite Dress”. A bitter, alcohol-soaked shot of jealousy and infidelity. Davey, being Davey, had gone for “A Million Miles”. Sung in the style of an all too familiar, awkward party pick up, a joyful story of love at first sight.

“Can’t Recall Days With Regret…”

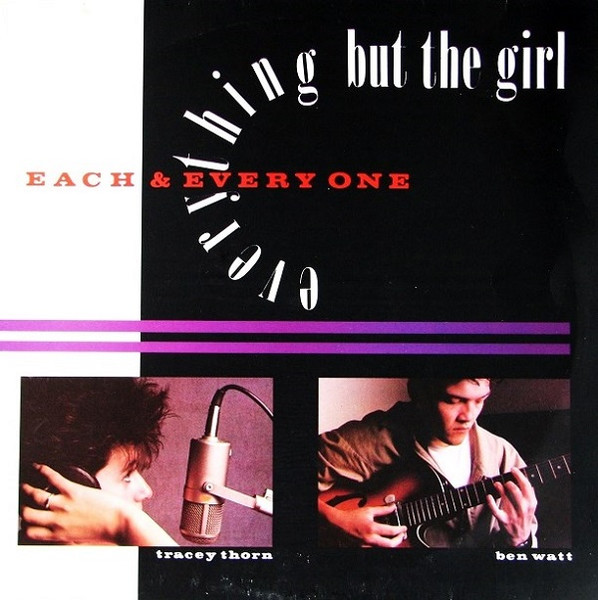

Everything But The Girl’s “Each & Everyone” was one of the songs that’d be on rotation, on the video jukebox, in The Three Tons. A busy, Beckenham pub, bustling with bright young things, the place was famous for having a folk club where David Bowie relaunched his career in the late `60s. No one here, though, was a Bowie freak or clone. This crowd hadn’t been born then. On a Friday and Saturday night the pub was packed, you could hardly move, and every corner held a different clique.

Bobby and Davey didn’t know anyone. Beckenham was actually a bit of a trek. But it was trendy, so they came. They didn’t get to know anybody either, except for the girls that they attempted to chat up, who’d roll their eyes, and return to their friends. All of them looking over laughing. Bobby and Davey took absolutely no notice. Davey was pretty thick-skinned and Bobby was usually plastered.

Tracey Thorn and Ben Watt were the king and queen of that indie bedsit bossa nova swing thing. Something Tracey had started perfecting while in The Marine Girls. Their “Don’t Come Back” was another song Bobby and Davey often played. Her lyrics were so clever. They both loved the way that she rhymed, singing, achingly, like an angel, of heartbreak and passion, obsession. Love grown cold.

“Another Bridge” was a coming of age cut. Friendships, shifting, changing, ending.

“You can’t hold on to everything…”

“Tomorrow remember today, and all the rest forget…”

There was no time for looking back. And at the time it didn’t feel like there was that much to look back on.

Discover more from Ban Ban Ton Ton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Lovely article, reminds me of careering round Belfast in the 70s and 80s.

LikeLike

Thank you. While very personal I was hoping it would touch on other folks experiences.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fucking hell Rob- I read this before work sitting at my desk and it nearly broke me in two. Brilliant writing. Post of the week.

LikeLike

Thanks Adam

LikeLike

Wow what a refreshing memorial to a great friend and an unvarnished reminder of what now feels like simpler times. Hopefully friends and family give you strength in tough times.

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike